目次

先看申明书。也能够比力挺拔氟胺和吗替麦考酚酯

有用过奥巴捷®挺拔氟胺的MS病友吗,最新申明书中多发性硬化患者数据怎么样? - 知乎 (zhihu.com)[1]

有用过奥巴捷®挺拔氟胺的MS病友吗,最新申明书中多发性硬化患者数据怎么样?1 附和 · 1 评论答复来氟米特/Leflunomide与甲氨蝶呤/Methotrexate有何区别?官方申明书差别?咋下载? - 知乎 (zhihu.com)[2]

来氟米特/Leflunomide与甲氨蝶呤/Methotrexate有何区别?官方申明书差别?咋下载?0 附和 · 0 评论答复吗替麦考酚酯与来氟米特的区别是什么? - 知乎 (zhihu.com)[3]

对本身免疫疾病,吗替麦考酚酯与来氟米特、挺拔氟胺的区别有什么?2 附和 · 0 评论答复 药品部 罗氏(roche.com.cn)[4]骁悉®吗替麦考酚酯胶囊申明书Mycophenolate Mofetil Capsules 2021年09月14日[5]骁悉®片Tablets[6]新版须药品部官网下载[4] 下载罗氏中国药品申明书:药品部官网www.roche.com.cn/zh_CN/disease-area/pharmaceuticals.html核准日期:2006年10月16日

修改日期:2007年11月07日

2008年01月22日

2008年12月15日

2009年12月14日

2010年01月18日

2011年09月14日

2012年07月16日

2013年05月08日

2014年10月24日

2015年12月01日

2016年06月03日

2016年11月11日

2018年02月01日

2018年08月08日

2018年11月27日

2019年10月21日

2020年04月10日

2020年10月01日

2020年11月11日

2020年12月30日

2021年06月07日

2021年09月14日

吗替麦考酚酯胶囊申明书

请认真阅读申明书并在医师指点下利用

警 告

免疫按捺剂会增加传染的易感性,可能促进淋巴瘤和其他肿瘤的发作。只要对免疫按捺治疗和对承受器官移植的患者有经历的专科医师才能够利用本品,患者应在装备响应的医疗设备和尝试室人员及可撑持的医疗前提下承受本品的治疗。负责病人持久随访的医师应掌握病人的全面信息以便对患者停止需要的随访。

因为本品具有致突变和致畸效应,具有生育才能的女性患者在起头利用本品停止治疗之前,须证明妊娠试验成果为阴性,并在起头利用本品前至停用本品后6周期间接纳避孕办法。在妊娠期间利用本品可能增加流产、先本性畸形等风险。

【药品名称】

通用名称:吗替麦考酚酯胶囊

商品名称:骁悉

英文名称:Mycophenolate Mofetil Capsules

汉语拼音:Matimaikaofenzhi Jiaonang

【成份】

化学名称:(E)-6-(4-羟基-6-甲氧基-7-甲基-3-氧代-1,3-二氢异苯并呋喃-5-基)-4-甲基-4-己烯酸 2-(吗啉-4-基)乙酯

化学构造式:

分子式:C23H31NO7

分子量:433.49

【性状】

本品为硬胶囊,内容物为白色或类白色块状物或(和)粉末。

【适应症】

本品与皮量类固醇以及环孢素或他克莫司同时应用,适用于治疗:

. 承受同种异体肾脏移植的患者中预防器官的排挤反响。

. 承受同种异体肝脏移植的患者中预防器官的排挤反响。

本品适用于III-V型成人狼疮性肾炎患者的诱导期治疗和维持期治疗。

【规格】

0.25 g

【用法用量】

已经证明吗替麦考酚酯具有致畸性感化,因而制止翻开吗替麦考酚酯胶囊或压碎胶囊。关于胶囊中的粉末,制止吸入或者间接接触皮肤或粘膜。若是发作接触,用肥皂和清水彻底清洗,并用清水冲刷眼睛。

关于和本品同时利用的皮量类固醇及环孢素或他克莫司,请参阅响应的完好处方信息。

肾脏移植:

成人:对肾移植受者,保举口服剂量为每次1g,每日2次(日剂量为2 g)。固然在临床试验顶用过每次1.5 g,每日2次(日剂量3 g),且是平安和有效的,但在肾脏移植中并没有效果上的优势。每天承受2 g本品的患者在总的平安性上比承受3 g的患者要好。

肝脏移植:

成人肝脏移植受者保举口服剂量为每次0.5~1 g,每日2次(日剂量1~2 g)。

在肾脏或肝脏移植后应尽早起头口服本品治疗。食物对麦考酚酸(MPA)AUC无影响,但使MPA Cmax下降40%。因而保举本品空腹服用。但是对不变的肾脏移植受者,若是需要本品能够和食物同服。

狼疮性肾炎患者:

诱导期治疗

成人保举剂量为每日1.5~2g,分两次口服给药。

本品凡是应与皮量类固醇结合利用。

维持期治疗

成人保举剂量为每日0.5~1.5g,分两次口服给药。

剂量调整:

肝损害患者

不建议对伴随严峻肝本色病变的肾脏移植受者调整剂量。但是,其他原因的肝脏疾病能否需要做剂量调整不清晰(见【药理毒理】和【药代动力学】)。

对伴随严峻肝本色病变的狼疮性肾炎患者尚无数据。

肾损害患者

关于有重度慢性肾脏损害(肾小球滤过率小于25ml/min/1.73m2)的肾移植受者,在渡过了术后早期后,或者对急性或难治性排挤反响停止治疗后,应制止利用大于每次 1g,每日2次的剂量。肾移植后移动物功用延迟恢复的患者,无需调整剂量,但那些患者需要严密察看。(见【药代动力学】)。

未获得重度肾损害的肝脏移植受者的数据。若是潜在的好处大于潜在的危害,重度慢性肾脏损害的患者同时承受肝脏移植后能够利用本品。

目前关于GFR <30 mL/min的狼疮性肾炎患者的数据尚不充实,如需利用本品,建议停止治疗药物浓度监测。

呈现中性粒细胞削减症的患者

若是呈现中性粒细胞削减(绝对中性粒细胞计数<1.3×103/μL),本品应暂停或减量,停止响应的诊断性查抄和恰当的治疗(见【留意事项】和【不良反响】)。

老年患者

适宜的肾脏移植受者保举剂量为每次1g,每日2次,肝脏移植受者为每次0.5~1 g,每日2次(见【老年用药】)。狼疮肾炎老年患者利用本品的数据尚不充实,暂无保举剂量。

【不良反响】

本章节所呈列的平安性特征基于来自临床试验和上市后经历的数据,且已被证明在移植患者人群和狼疮性肾炎患者人群中类似。

临床试验

在预防急性器官排挤的关键临床试验中,估量共有1557例患者承受本品治疗。此中991例患者被纳入到汇总肾脏移植研究ICM1866、MYC022和MYC023中,277例患者被纳入到肝脏移植研究MYC2646中,以及289例患者被纳入到心脏移植研究MYC1864中。所有研究组的患者还承受环孢素和皮量类固醇治疗。

腹泻、白细胞削减症、脓毒症以及吐逆是关键试验中与本品给药相关的最常见和/或严峻药物不良反响。

还有证据表白特定类型传染的发作频次较高,例如,时机性传染等(见【留意事项】)。

在预防肾脏移植排挤反响的3项关键试验中,承受每日2 g本品治疗患者的平安性特征,在总体上优于承受3 g本品治疗的患者。利用本品治疗难治性肾脏移植排挤反响的患者平安性特征,与预防肾脏排挤反响的关键试验中察看到的特征类似,在该项试验中,利用的剂量为每日为每日为每日为每日

临床试验的药物不良反响汇总表

根据MedDRA系统器官分类及其发作率列出了临床试验中的药物不良反响。各药物不良反响的响应频次分类是基于下述老例:非常常见(≥1/10);常见(≥1/100至<1/10);偶见(≥1/1,000至<1/100);稀有(≥1/10,000至<1/1,000);非常稀有(<1/10,000)。因为察看到差别移植适应症的某些ADR频次存在庞大差别,因而零丁列出了肾脏、肝脏和心脏移植受者的药物不良反响频次。

关键临床试验中承受本品治疗的患者的药物不良反响汇总

药物不良反响

(MedDRA)

系统器官分类

肾脏移植

n = 991

肝脏移植

n = 277

心脏移植

n = 289

发作率(%)

频次

发作率(%)

频次

发作率(%)

频次

传染及侵染类疾病

各类细菌传染

39.9

非常常见

27.4

非常常见

19.0

非常常见

各类实菌传染

9.2

常见

10.1

非常常见

13.1

非常常见

各类病毒传染

16.3

非常常见

14.1

非常常见

31.1

非常常见

良性、恶性及性量不明的肿瘤(包罗囊状和息肉状)

良性皮肤肿瘤

4.4

常见

3.2

常见

8.3

常见

肿瘤

1.6

常见

2.2

常见

4.2

常见

皮肤癌

3.2

常见

0.7

偶见

8.0

常见

血液及淋巴系统疾病

贫血

20.0

非常常见

43.0

非常常见

45.0

非常常见

瘀斑

3.6

常见

8.7

常见

20.1

非常常见

白细胞增加症

7.6

常见

22.4

非常常见

42.6

非常常见

白细胞削减症

28.6

非常常见

45.8

非常常见

34.3

非常常见

全血细胞削减症

1.0

常见

3.2

常见

0.7

偶见

假性淋巴瘤

0.6

偶见

0.4

偶见

1.0

常见

血小板削减症

8.6

常见

38.3

非常常见

24.2

非常常见

代谢及营养类疾病

酸中毒

3.4

常见

6.5

常见

14.9

非常常见

高胆固醇血症

11.0

非常常见

4.7

常见

46.0

非常常见

高血糖症

9.0

常见

43.7

非常常见

48.4

非常常见

高钾血症

7.3

常见

22.0

非常常见

16.3

非常常见

高脂血症

7.6

常见

8.7

常见

13.8

非常常见

低钙血症

3.2

常见

30.0

非常常见

8.0

常见

低钾血症

7.8

常见

37.2

非常常见

32.5

非常常见

低镁血症

1.8

常见

39.0

非常常见

20.1

非常常见

低磷酸血症

10.8

非常常见

14.4

非常常见

8.7

常见

体重降低

1.0

常见

4.7

常见

6.2

常见

神经病类

意识模糊形态

1.4

常见

17.3

非常常见

14.2

非常常见

抑郁

3.7

常见

17.3

非常常见

20.1

非常常见

失眠

8.4

常见

52.3

非常常见

43.3

非常常见

各类神经系统疾病

头晕

7.8

常见

16.2

非常常见

34.3

非常常见

头痛

14.8

非常常见

53.8

非常常见

58.5

非常常见

高张力

3.3

常见

7.6

常见

17.3

非常常见

觉得错乱

6.3

常见

15.2

非常常见

15.6

非常常见

嗜睡

2.6

常见

7.9

常见

12.8

非常常见

震颤

9.2

常见

33.9

非常常见

26.3

非常常见

心脏器官疾病

心动过速

4.3

常见

22.0

非常常见

22.8

非常常见

血管与淋巴管类疾病

高血压

27.5

非常常见

62.1

非常常见

78.9

非常常见

低血压

4.9

常见

18.4

非常常见

34.3

非常常见

静脉血栓构成*

4.4

常见

2.5

常见

2.4

常见

呼吸系统、胸及纵隔疾病

咳嗽

11.4

非常常见

15.9

非常常见

40.5

非常常见

呼吸困难

12.2

非常常见

31.0

非常常见

44.3

非常常见

胸腔积液

2.2

常见

34.3

非常常见

18.0

非常常见

胃肠系统疾病

腹痛

22.4

非常常见

62.5

非常常见

41.9

非常常见

结肠炎

1.6

常见

2.9

常见

2.8

常见

便秘

18.0

非常常见

37.9

非常常见

43.6

非常常见

食欲下降

4.7

常见

25.3

非常常见

14.2

非常常见

腹泻

30.4

非常常见

51.3

非常常见

52.6

非常常见

消化不良

13.0

非常常见

22.4

非常常见

22.1

非常常见

食管炎

4.9

常见

4.3

常见

9.0

常见

肠胃气胀

6.4

常见

18.8

非常常见

18.0

非常常见

胃炎

4.4

常见

4.0

常见

9.3

常见

胃肠出血

2.7

常见

8.3

常见

7.6

常见

胃肠溃疡

3.1

常见

4.7

常见

3.8

常见

肠梗阻

2.4

常见

3.6

常见

2.4

常见

恶心

18.4

非常常见

54.5

非常常见

56.1

非常常见

口腔黏膜炎

1.4

常见

1.4

常见

3.5

常见

吐逆

10.6

非常常见

32.9

非常常见

39.1

非常常见

肝胆系统疾病

血碱性磷酸酶升高

5.2

常见

5.4

常见

9.3

常见

血乳酸脱氢酶升高

5.8

常见

0.7

偶见

23.5

非常常见

肝酶升高

5.6

常见

24.9

非常常见

17.3

非常常见

肝炎

2.2

常见

13.0

非常常见

0.3

偶见

皮肤及皮下组织类疾病

脱发

2.2

常见

2.2

常见

2.1

常见

皮疹

6.4

常见

17.7

非常常见

26.0

非常常见

各类肌肉骨骼及结缔组织疾病

关节痛

6.4

常见

6.1

常见

10.0

非常常见

肌无力

3.0

常见

4.0

常见

13.8

非常常见

肾脏及泌尿系统疾病

血肌酐升高

8.2

常见

19.9

非常常见

42.2

非常常见

血尿素升高

0.8

偶见

10.1

非常常见

36.7

非常常见

血尿

10.0

非常常见

5.1

常见

5.2

常见

全身性疾病及给药部位各类反响

乏力

10.8

非常常见

35.4

非常常见

49.1

非常常见

寒噤

2.0

常见

10.8

非常常见

13.5

非常常见

水肿

21.0

非常常见

48.4

非常常见

67.5

非常常见

疝气

4.5

常见

11.6

非常常见

12.1

非常常见

不适

2.4

常见

5.1

常见

9.0

常见

痛苦悲伤

9.8

常见

46.6

非常常见

42.2

非常常见

发热

18.6

非常常见

52.3

非常常见

56.4

非常常见

*静脉给药后陈述的不良事务。

选定的药物不良反响描述

传染

所有承受免疫按捺剂治疗患者的细菌、病毒和实菌传染(此中一些可能招致致死性结局)风险增加,包罗由时机性传染药物和暗藏病毒再活化招致的传染(见【留意事项】)。风险随免疫按捺负荷增加而加大(见【留意事项】)。最严峻的传染为脓毒症和腹膜炎。承受本品和其他免疫按捺剂结合治疗患者的最常见时机性传染是皮肤黏膜念珠菌病,巨细胞病毒血症/综合征和单纯疱疹病毒传染。此中巨细胞病毒血症/综合征的患者比例占13.5%。

恶性肿瘤

承受本品和其他免疫按捺剂结合治疗的患者,发作淋巴瘤和其他恶性肿瘤的危险性增加,尤其是发作皮肤恶性肿瘤的危险性增加(见【留意事项】)。

在肾脏和心脏移植受者的3年平安性数据中,恶性肿瘤的发作率与1年的数据比拟,并没有发现任何非预期的改动。在肝脏移植受者均随访了1年以上,3年以下。

在治疗难治性肾移植排挤反响的撑持性临床试验中,均匀随访为期42个月的淋巴瘤发作率为3.9%。

血液和淋巴系统疾病

包罗白细胞削减症、贫血、血小板削减症和全血细胞削减症在内的血细胞削减症是麦考酚酯相关的已知风险,可能招致或促使传染和出血的发作(见【留意事项】)。

胃肠系统疾病

最严峻的胃肠系统疾病是溃疡和出血,那是本品相关的已知风险。在关键临床试验中,常陈述口腔、食管、胃、十二指肠和肠溃疡凡是并发出血、以及呕血、黑粪症、出血性胃炎和结肠炎。但最常见的胃肠系统疾病为腹泻、恶心和吐逆。对本品相关腹泻患者停止内窥镜检发现个别肠道绒毛萎缩病例(见【留意事项】)。

全身性疾病及给药部位各类反响

关键试验中陈述的非常常见的不良反响为水肿,包罗外周、面部和阴囊水肿。已陈述的包罗诸如肌痛和颈背痛在内的肌肉骨骼痛苦悲伤也是非常常见的不良反响。

特殊人群

儿童 (年龄在3个月到18周岁之间)

在对100名3个月到18周岁之间的儿科患者停止的临床研究中,赐与600 mg/m2 吗替麦考酚酯每日两次口服以后,呈现的不良药物反响的类型和频次,在整体上与赐与1克本品每日两次口服的成人患者中察看到的不良反响都是类似的。但是,以下在儿童傍边呈现的频次≥10%的治疗相关不良事务,与成人中呈现的治疗相关不良事务的频次比拟,在儿科人群出格是在6周岁以下的儿童傍边愈加常见,包罗:腹泻,白细胞削减症,败血症,传染以及贫血。

老年患者(≥65周岁)

同年轻人比拟,老年人,尤其是承受本品做为结合免疫按捺计划一部门的患者,某些传染(包罗巨细胞病毒组织侵袭病)、可能的胃肠出血和肺水肿的危险增加(见【留意事项】)。

上市后经历

根据MedDRA中的系统器官分类列出药物不良反响,且各药物不良反响的响应频次分类估量是基于下述老例:非常常见(≥1/10);常见(≥1/100至<1/10);偶见(≥1/1,000至<1/100);稀有(≥1/10,000至 <1/1,000);非常稀有(<1/10,000)。

上市后经历中确定的药物不良反响

药物不良反响

(MedDRA)

系统器官分类

发作率(%)

频次分类

传染及侵染类疾病

原虫传染

N/A

偶见2

良性、恶性及性量不明的肿瘤(包罗囊状和息肉状)

淋巴肿瘤

N/A

偶见2

淋巴增生疾病

N/A

偶见2

血液及淋巴系统疾病

单纯红细胞再生障碍性贫血

N/A

偶见2

骨髓功用衰竭

N/A

偶见2

胃肠系统疾病

胰腺炎

1.801

常见

免疫系统疾病

超敏反响

3.101

常见

低丙球卵白血症

0.401

偶见

呼吸系统、胸及纵隔疾病

收气管扩张

N/A

偶见2

间量性肺病

0.201

偶见

肺纤维化

0.401

偶见

血管与淋巴管类疾病

淋巴囊肿

N/A

偶见2

全身性疾病及给药部位各类反响

嘌呤从头合成按捺剂相关性急性炎症综合征

N/A

偶见2

1在关键临床试验期间察看到的更高发作率

2 仅在上市后情况中察看到的ADR的频次分类被定义为基于关键试验中表露于本品的患者总数计算的95%置信区间上限。

传染:

严峻的威胁生命的传染,例如脑膜炎和传染性心内膜炎偶有报导,有证据表白必然类型的传染如结核和非典型分枝杆菌传染有较高的发作率。

在利用本品治疗的患者中有陈述停止性多灶性白量脑病(PML)和BK病毒性肾病(见【留意事项】)。

先本性疾病和妊娠期、产褥期及围产期:

见(【妊妇及哺乳期妇女用药】)获取进一步信息。

全身性疾病及给药部位各类反响:

嘌呤从头合成按捺剂相关性急性炎症综合征是一种新描述的麦考酚酸(MPA)及其他嘌呤合成按捺剂相关的异常促炎反响,其表示为发热、关节痛、关节炎、肌肉痛和炎症标记物升高。据文献陈述,停药后那些症状敏捷改善。

狼疮性肾炎研究

吗替麦考酚酯在国外停止的ALMS(Aspreva Lupus Management Study/NCT00377637)研究,是一项前瞻性随机对照全球多中心研究。研究详情见临床试验部门。

本部门所列平安性信息,均为临床试验中受试者承受药物治疗后发作的所有不良事务,不良事务与治疗之间纷歧定有因果联系关系。

1. 诱导期研究

诱导治疗期内,承受口服MMF(吗替麦考酚酯)治疗的患者共184例,承受静脉输注CTX(环磷酰胺)治疗的患者共180例。

平安性成果

两组间的不良事务比例未呈现显著差别(MMF组为96.2%,CTX组为95.0%)。最常见的不良事务类型均为传染(MMF组为68.5%,CTX组为61.7%)和胃肠系统疾病(MMF组为61.4%,CTX组为66.7%)。MMF组和CTX组的腹泻发作率别离为28.3%和12.8%,两组无统计学差别。MMF组和CTX组别离有27.7%和22.8%的患者发作至少1例严峻不良事务:2个治疗组中最常陈述的严峻不良事务类型均为传染,MMF组和CTX组的传染发作率别离为12.0%和10.0%;MMF组和CTX组的胃肠系统疾病的发作率别离为4.3%和1.7%,肾脏和泌尿系统疾病的发作率别离为4.3%和1.7%。MMF组和CTX组别离有24例(13.0%)和13例(7.2%)不良事务招致的退出。MMF组和CTX组别离有9例(4.9%)和5例(2.8%)灭亡,无显著统计学差别。在MMF组中,7例(3.8%)灭亡是因为传染所致,1例(0.5%)灭亡是因为间量性肺病所致,1例(0.5%)灭亡原因不详。在CTX组中,发作了2例(1.1%)传染招致的灭亡和2例(1.1%)系统性红斑狼疮招致的灭亡。MMF组中的7/9例(77.8%的灭亡患者)灭亡发作在亚洲。重度基线病症(32例患者的GFR为30 ml/min/1.73 m2)以及严峻的系统性红斑狼疮根底疾病以及快速恶化的呼吸道症状为该差别的可能的原因。阐发表白,以及严峻的系统性红斑狼疮根底疾病以及快速恶化的呼吸道症状为该差别的可能的原因。阐发表白,以及严峻的系统性红斑狼疮根底疾病以及快速恶化的呼吸道症状为该差别的可能的原因。阐发表白,以及严峻的系统性红斑狼疮根底疾病以及快速恶化的呼吸道症状为该差别的可能的原因。阐发表白,以及严峻的系统性红斑狼疮根底疾病以及快速恶化的呼吸道症状为该差别的可能的原因。阐发表白,以及严峻的系统性红斑狼疮根底疾病以及快速恶化的呼吸道症状为该差别的可能的原因。阐发表白,

2. 维持期研究

维持治疗期内,最末共226例诱导治疗后到达缓解的患者被随机分配承受治疗,115例患者承受MMF口服造剂,111例患者承受AZA(硫唑嘌呤)口服胶囊剂。

平安性成果

两组的治疗期间不良事务发作率类似:承受MMF治疗的患者为98.3%(113例),承受AZA治疗的患者为97.3%(108例)。两组最常见的不良事务均为传染,传染在MMF组和AZA组发作率别离为79.1%和78.4%。MMF组和AZA组的严峻传染发作率别离为9.6%和11.7%。AZA治疗组中,发作因不良事务招致退出的患者比例(39.6%)高于MMF治疗组(25.2%)。MMF组中发作至少1例严峻不良事务的患者数量少于AZA组,但无统计学差别(MMF组和AZA组别离为23.5%和33.3%)。

【禁忌】

本品禁用于已知关于吗替麦考酚酯、麦考酚酸或本品中任何成份过敏者。

本品禁用于妊妇。

本品禁用于未利用高效避孕办法的育龄期妇女。

本品禁用于哺乳期妇女。

【留意事项】

留意:本品用于治疗狼疮性肾炎时,应由具有狼疮性肾炎治疗经历的专科医生停止给药。

在包拆上标明的有效期后不克不及再服用。

药品请存放于小孩接触不四处。

淋巴瘤及其他肿瘤:

承受免疫按捺剂治疗的患者,包罗结合用药,承受本品做为部门免疫按捺治疗,发作淋巴瘤及其它恶性肿瘤的危险性增加,尤其是皮肤(见【不良反响】)。危险性与免疫按捺的强度和疗程有关,而与特定的免疫按捺剂无关。

因为患者发作皮肤癌的危险性增加,应通过穿防护衣或含高防护因子的防晒霜来削减表露于阳光和紫外线下。

传染:

免疫系统的过度按捺可增加对传染的易感性,包罗前提时机性传染,致死传染和败血症。那种传染包罗暗藏病毒的再激活,如乙肝或丙肝病毒的再激活,或多瘤病毒引起的传染。已有利用免疫按捺剂治疗的肝炎病毒照顾者因乙肝或丙肝病毒再激活引发肝炎的病例报导。那种传染包罗暗藏病毒的再激活,如乙肝或丙肝病毒的再激活,或多瘤病毒引起的传染。已有利用免疫按捺剂治疗的肝炎病毒照顾者因乙肝或丙肝病毒再激活引发肝炎的病例报导。

利用本品治疗的患者中,有发作与JC病毒相关的停止性多灶性白量脑病(PML)病例中报导,且部门病例为致死性病例,PML凡是表示为轻偏瘫、冷淡、意识模糊、认知障碍和共济失调。陈述的病例一般具有PML的危险因素,包罗免疫按捺剂疗法和免疫功用缺损。关于免疫按捺患者,医生应考虑对陈述有神经症状的患者采纳PML辨别诊断,还应请神经病学家赐与专科专家定见。

在肾移植后利用本品治疗的患者中有BK病毒相关性肾病的报导,那种传染可能形成严峻的后果,有时候可能招致肾移植失败。对病人停止监测有助于发现其罹患BK病毒相关性肾病的风险。因为MPA对B淋巴细胞和T淋巴细胞的增殖具有按捺感化,COVID-19的严峻度可能会增加。关于有确诊BK病毒相关性肾病迹象或发作具有临床意义的COVID-19传染的患者应考虑降低MPA剂量或末行给药。

血液及免疫系统:

在每日承受3g本品治疗的肾移植受者和肝移植受者中,别离有2.0%、3.6%患者呈现严峻中性粒细胞削减症[中性粒细胞计数(ANC)<0.5×103/μL]。患者在承受本品治疗的第一个月内,应每周完成一次全血细胞计数查验;在治疗的第二个月和第三个月内,应每月完成两次查验;然后至一年时,应每月完成一次查验。应出格监测中性粒细胞削减症的呈现情况(见【留意事项】:尝试室查验)。中性粒细胞削减症的呈现可能与本品有关,也可能与合用药物、病毒传染或综合原因等有关。若是呈现中性粒细胞削减症(ANC <1.3 × 103/μL),应中断本品给药,或降低剂量并亲近察看(见【用法用量】)。察看到预防肾移植或肝移植排异反响患者最常呈现中性粒细胞削减症的时间是移植后31~180天。

在承受本品结合其他免疫按捺剂治疗的患者中,有报导发作单纯红细胞再生障碍(PRCA)。本品招致PRCA的机理尚不清晰;其他免疫按捺剂做为结合应用药物在免疫按捺治疗中引起PRCA的相关感化也尚不清晰。在一些病例中,跟着本品剂量的减小或中行,发现PRCA是可逆的。然而,关于移植受者,降低免疫按捺感化可能使移动物遭受排挤风险增大。

应告知承受本品治疗的患者,在呈现任何传染症状、不测瘀肿、出血、其他骨髓按捺或胃肠道症状时应立即报告请示。

献血:

患者在治疗期间以及本品停药后至少6周内不该献血。

疫苗接种:

患者应被告知在本品治疗中停止疫苗接种可能效果欠佳。并且应当制止利用减毒活疫苗(见【药物彼此感化】)。流感疫苗接种是有益的。流感疫苗接种时,处方者应当参考国度指南。

消化系统:

本品同消化系统不良反响的发作率增高有关,包罗稀有的胃肠道溃疡、出血、穿孔,所以本品应慎用于有活动性消化系统疾病的患者。

理论上讲,因为本品是次黄嘌呤单核苷酸脱氢酶(IMPDH)按捺剂,应制止用于有稀有的次黄嘌呤-鸟嘌呤磷酸核糖转移酶(HGPRT)遗传缺陷的患者,如莱-尼综合征和Kelley-Seegmiller综合征。

彼此感化:

含有本品的结合免疫按捺计划转换时需隆重,因为部门药物能够影响MPA肝肠轮回,例如将环孢素转换为他克莫司、西罗莫司或贝拉西普,则能够制止干扰 MPA的肝肠轮回 ;或者反之,则可能招致MPA表露的变革(见【药物彼此感化】)。

当转换结合治疗时(例如,从环孢素转换为他克莫司,或反之亦然),或者为了确保高免疫风险患者(例如,排挤风险,抗生素治疗,新增或移除彼此感化药物)获得充实的免疫按捺时,可能需要对MPA停止治疗药物监测。

当本品与干扰MPA肝肠轮回的其他类型药物(如消胆胺、司维拉姆、抗生素)结合利用时应隆重,因为那些药物可能会降低本品的血浆浓度和疗效(见【药物彼此感化】)。应在服用本品2小时后应用司维拉姆和其他非钙性磷酸盐连系剂,从而将其对MPA吸收的影响降至更低。

不保举本品和硫唑嘌呤结合利用,因为两者都可能引起骨髓按捺,尚未对此结合给药停止临床研究。

特殊人群用药:

老年患者:

老年患者发作某些传染(包罗巨细胞病毒组织侵袭性疾病),可能的胃肠道出血和肺水肿等不良事务的危险性高于年轻患者(见【不良反响】)。肿等不良事务的危险性高于年轻患者(见【不良反响】)。

妊妇和哺乳期妇女:

本品禁用于妊妇和哺乳期妇女(见【妊妇及哺乳期妇女用药】)。

捐精

男性患者在治疗期间以及停用本品后90天内不得捐精。

药物滥用和依赖性:

无可用数据表白本品存在药物滥用和依赖性的可能性。

对驾驶和机器操做才能的影响:

本品可对驾驶和机器操做才能产生中度影响。

若是患者在承受本品治疗期间呈现嗜睡、意识模糊、头晕、震颤或低血压等药物不良反响,应建议患者在驾驶或操做机器时慎用本品(见【不良反响】)。

具有生育才能的女性和男性:

生育力

本品制止用于未利用高效避孕办法的育龄期妇女(见【禁忌】)。承受吗替麦考酚酯经口给药的雌性大鼠的第一代子代呈现畸形(包罗无眼、无颌和脑积水),但未呈现母体毒性。未察看到对承受吗替麦考酚酯给药的雄性大鼠的生育力产生影响。

妊娠试验

具有生育才能的女性患者在起头利用本品停止治疗之前,必需有一次血清或尿液妊娠试验检测阴性成果,且灵敏度至少为25 mlU/mL。第二次检测应在初次检测后8~10天。患者在常规随访过程中,应反复停止妊娠试验检测。医生应就所有妊娠试验成果与患者停止讨论。患者应充实知悉,怀孕后需立即征询医生。

避孕

. 女性

本品制止用于未利用高效避孕办法的育龄期妇女(见【禁忌】)。

具有生育才能的女性患者在起头利用本品停止治疗前,必需充实知悉本品会增加妊娠丧失和先本性畸形的风险,必需向医生征询关于避孕和怀孕的建议。建议有生育才能的女性患者在起头利用本品停止治疗之前,治疗期间及治疗末行后6周内,应同时接纳两种可靠的避孕办法,此中至少包罗一种高效办法,或是选择禁欲做为避孕办法。那也包罗有不育症病史的患者,已行子宫切除术的患者无需避孕。

. 男性

目前关于父亲表露于本品的临床数据有限。那些数据未提醒父亲表露于麦考酚酯后畸形或流产的风险增加。

非临床数据表白,通过精液转移至可能妊娠朋友的麦考酚酯剂量是动物中无致畸感化浓度的1/30,是动物中更低致畸浓度的1/200。因而,认为通过精液招致损害的风险可忽略不计。但是,在表露量大约为人体治疗表露量的2.5倍的动物研究中,察看到遗传毒性效应。因而,不克不及完全排除对精子细胞产生遗传毒性效应的风险。

因数据不敷,无法排除父亲治疗期间或治疗之后对受孕胎儿产生危险的风险,建议采纳以下预防办法:

建议性活泼的男性患者在治疗期间及治疗末行后至少90天内利用避孕套停止避孕。避孕套既适用于具有生殖才能的男性患者,也适用于输精管结扎术后的男性患者,因为输精管结扎术后的男性患者也可能存在致孕的相关风险。此外,建议男性患者的女性朋友在其治疗期间及最初一剂本品给药后至少90天内采纳高效的避孕办法。

患者信息:

. 为患者出示完好给药申明,同时告知患者淋巴增素性疾病和某些其他恶性肿瘤的风险可能增加。

. 告知患者,在承受本品治疗期间,需要患者频频承受尝试室查验。

. 告知育龄妇女,当在怀孕期间利用本品时,可能在前3个月内增加流产风险,还增加出生缺陷风险,他们必需采纳有效避孕办法。

. 与育龄女性患者参议怀孕方案。 . 在起头承受本品前4周内,育龄妇女必需采纳高效避孕办法(同时采纳两种办法),当本品停行治疗后6周内,还必需继续采纳避孕办法(见【妊妇及哺乳期妇女用药】)。

. 方案怀孕患者不该承受本品治疗,除非接纳其他免疫按捺剂不克不及胜利治疗。

尝试室查验:

在治疗的第一个月,应每周完成一次全血细胞计数,在治疗的第二个月和第三个月内,应每月完成两次查验,然后至一年时每月完成一次查验。

【妊妇及哺乳期妇女用药】

生育力、妊娠试验和避孕见【留意事项】。

致畸效应:妊娠分类 D(FDA分类)

动物研究表白本品具有生殖毒性。在动物生殖毒理学研究中,当无母体毒脾气况下,胎儿吸收和畸形的发作率升高。按照体外表积转换,雌性大鼠和雌性兔子承受的吗替麦考酚酯(MMF)剂量相当于肾移植受者所承受人用剂量的0.02~0.9倍。在大鼠子代中发作的畸形包罗无眼、无下颌和脑积水。在兔子子代中发作的畸形包罗心脏异位、肾脏异位、膈疝和脐疝。

妊妇

因为本品具有致突变和致畸的可能性,妊娠期内制止利用本品(见【禁忌】)。本品为人体致畸物,会增加天然流产风险(次要是妊娠早期),并且若是在妊娠期内发作母体表露会招致先天畸形(见【上市后经历】)。按照医学文献报导,在利用吗替麦考酚酯治疗的妊娠患者中,天然流产的陈述率为45~49%;而在利用其他免疫按捺剂治疗的实体器官移植受者中,天然流产的陈述率为12~33%。

按照已颁发文献报导,在利用吗替麦考酚酯治疗的妊娠患者中,活产胎儿先天畸形率(包罗个别重生儿的多发畸形)为23~27%。在总人群中,活产胎儿畸形率为2%;在利用吗替麦考酚酯之外的其他免疫按捺剂治疗的实体器官移植受者中,活产胎儿畸形率约为4~5%。

上市后已经报导了妊娠期内承受吗替麦考酚酯和其他免疫按捺剂结合治疗的患者的子女中,呈现先本性畸形,包罗多发畸形的情况。

最常报导的畸形相关的不良事务,如下所述:

. 面部畸形,(例如唇裂、上腭裂、小颌畸形和眼距增宽)

. 耳部异常,(例如外耳/中耳发育异常或缺如)和眼部异常(例如眼组织缺损、小眼症)

. 手指畸形,(例如多指畸形、并指、短指、短趾)

. 心脏畸形,(例如房间隔缺损、室间隔缺损)

. 食管畸形,(例如食管闭锁)

. 神经系统畸形,(例如脊柱裂)

上述成果与大鼠和家兔致畸性研究的成果一致,在那些研究中,发作了胚胎吸收和畸形,但未发作母体毒性。

临蓐:尚未确定本品在临蓐期间利用的平安性。

哺乳期妇女

对大鼠的研究发现本药可从乳汁平分泌。但尚不知在人类中本药能否会排泄到母乳中。因为本品可能会招致哺乳期婴儿发作严峻不良反响,所以本品禁用于哺乳期妇女(见【禁忌】)。

【儿童用药】

按照肾脏移植后儿童的药代动力学和平安性数据,保举剂量是吗替麦考酚酯口服每次600 mg/m2,每日2次(更大至每次1g,每日2次)(拜见【用法用量】、【不良反响】、【临床试验】和【药理毒理】)。

在承受肝脏同种异体移植的儿童患者的平安性和有效性尚未确定。

目前狼疮性肾炎儿童患者的平安性和有效性尚不充实。不保举儿童利用。

【老年用药】

本品的临床试验中未包罗足够的65岁或以上的老年人,不克不及确定老年人的效果能否与年轻人差别。其他报导的临床经历也没有确定老年人和年轻人的效果差别。总的来说,老年人的剂量选择要稳重,因为老年人的肾脏、心脏和肝脏功用下降和合并应用其他药物的情况较年轻人更多。与年轻人比拟,老年人的不良反响可能更多见。

拜见【用法用量】、【不良反响】和【留意事项】。

【药物彼此感化】

DNA聚合酶按捺剂(阿昔洛韦、更昔洛韦)

阿昔洛韦:同时服用本品和阿昔洛韦,酚化葡萄糖醛麦考酚酸(MPAG)和阿昔洛韦的血浆浓度均较零丁用药时有所升高。因为肾损害时,MPAG 血浆浓度升高,阿昔洛韦浓度也升高,所以两种药物合作从肾小管排泄的潜在性的存在,使两种药物的血浆浓度可能进一步升高。

更昔洛韦:按照保举剂量的单剂口服吗替麦考酚酯和静注更昔洛韦的研究成果,和已知肾损害对本品(见【药代动力学】和【留意事项】)与更昔洛韦药代动力学的影响,估计那些试剂的结合给药(合作肾小管排泄的机造)将招致MPAG和更昔洛韦浓度的增加。估计MPA药代动力学没有本色性改动,也无需调整本品的剂量。在肾损害的患者傍边,本品与更昔洛韦或者它的前药,如缬更昔洛韦结合给药时,应对其停止认真监视。

抗酸药和量子泵按捺剂(PPI)

同时服用本品和抗酸药(如氢氧化镁和氢氧化铝)或量子泵按捺剂(包罗兰索拉唑和泮托拉唑)时,能够察看到托拉唑)时,能够察看到托拉唑)时,能够察看到托拉唑)时,能够察看到托拉唑)时,能够察看到托拉唑)时,能够察看到托拉唑)时,能够察看到托拉唑)时,能够察看到

螯合剂

消胆胺:一般安康受试者,预先服用消胆胺4天,每次4g,每日3次,单剂给药本品1.5 g,MPA的AUC下降约40%。本品与影响肝肠轮回的药物合用时需稳重(见【留意事项】)。

司维拉姆:在成人和儿童患者中,合并利用司维拉姆和本品能够使MPA的Cmax和AUC0~12 别离降低30%和25%(见【留意事项】)。那些数据表白,应在服用本品后2小时应用司维拉姆和其他钙游离磷酸盐连系剂,从而将其对MPA吸收的影响降至更低。

免疫按捺剂

环孢素A:环孢素A(CsA)的药代动力学不受本品的影响。但在肾移植受者中,与结合利用西罗莫司或贝拉西普类似剂量本品的患者比拟,合并利用本品和环孢素A,因为环孢素A干扰MPA的肝肠轮回,可将MPA降低30~50%。相反地,患者从环孢素A转为不干扰MPA肝肠轮回的免疫按捺剂时,预期MPA的表露量会发作变革。

他克莫司:在承受肝脏移植的患者中,合并利用他克莫司和本品对MPA 的AUC或Cmax没有影响。比来在肾移植受者中停止的一项研究也察看到了类似成果。

在肾移植受者中发现,本品不会改动他克莫司的浓度。

但是在肝脏移植受者中,赐与他克莫司服用者多剂本品(每次1.5 g,每日2次)后,他克莫司的AUC大约增加20%。

抗生素

利福平:颠末剂量校正以后,在单心肺移植的患者合并利福平给药时察看到MPA 的表露(AUC0~12h)下降了70%。因而建议在合并利用此药的时候,对MPA的表露程度停止监测,并响应地调整本品的剂量,以维持临床疗效。

小肠内肃清产β-葡萄糖醛酸酶细菌的抗生素(如:氨基糖苷、头孢菌素、氟喹诺酮和青霉素类)可能会干扰MPAG/MPA肠肝轮回,进一步招致MPA全身表露削减(见【留意事项】、【彼此感化】)。

有关下述抗生素的可用信息:

环丙沙星或阿莫西林克拉维酸:据报导,肾脏移植受者口服环丙沙星或阿莫西林克拉维酸后,MPA初始剂量浓度(谷值)在服药当天随即降低54%。持续服用抗生素,那一感化有削弱的趋向,停药后该感化消逝。初始剂量程度的改动可能其实不能准确反映MPA的全身表露量,因而尚不清晰那些察看成果的临床相关性。

诺氟沙星和甲硝唑:单次赐与本品后,结合利用诺氟沙星和甲硝唑招致MPA的AUC0-48降低30%。将本品与此中任何一种抗生素零丁结合利用不会对MPA全身表露产生影响。

甲氧苄啶/磺胺甲基异噁唑:结合利用甲氧苄啶/磺胺甲基异噁唑时,对MPA(AUC,Cmax)的全身表露量无影响。

口服避孕药

口服避孕药的药代动力学不受同服本品的影响。18例银屑病的妇女超越3个月经周期的研究表白,本品 (每次1g,每日2次)与含有乙炔雌醇(0.02~0.04 mg)和左炔诺孕酮(0.05~0.20 mg),去氧孕烯(0.15 mg)或孕二烯酮(0.05~0.10 mg)的连系型口服避孕药结合给药,血清黄体酮、LH和FSH程度无显著影响,表示本品对口服避孕药的卵巢按捺功用可能无影响。

其他彼此感化

合用可按捺MPA葡萄糖苷酸化的药物可能会增加MPA表露量(例如,合用艾沙康唑时,MPA AUC0-∞增加35%)。因而,此类药物与本品合用时应隆重。

与替米沙坦联用,可使MPA的浓度降低大约30%。替米沙坦能够改动MPA的消弭,是通过进步PPAR γ表达(过氧化物酶体增殖物活化受体γ),然后招致UGT1A9 表达和活性的增加,从而加强葡萄糖苷酸化感化。将赐与本品联用替米沙坦及不联用替米沙坦患者的移植排挤的发作率、移植失败的发作率或者不良反响停止比照,没有察看到药代动力学药物彼此感化(DDI)的临床成果。

本品与丙磺舒合用,在山公试验中可使血浆MPAG AUC升高3倍。因而,其他已知从肾小管排泄的药物都可能与MPAG合作,因而可使MPAG和其他通过肾小管排泄的药物血浆浓度升高。

活疫苗:免疫反响损伤的患者不该当利用活疫苗。对其他疫苗的抗体反响也可能会削减。

【药物过量】

临床试验及上市后经历中已有吗替麦考酚酸酯过量的陈述。此中许多病例没有不良事务。在陈述了不良事务的药物过量病例中,不良事务属于药物已知的平安性范畴特征。

估量吗替麦考酚酸酯过量可能会招致免疫系统的过度按捺,增加传染和骨髓按捺的易感性(见【留意事项】)。若是呈现中性粒细胞降低,请停用本品或削减剂量(见【留意事项】)。

血液透析不克不及肃清MPA。但是,若是MPAG血浆浓度较高(大于100 μg/ml),则能够肃清少量MPAG。别的,通过增加药物的排泄,MPA可被胆酸连系剂消弭,如消胆胺(见【药代动力学】)。

【临床试验】

多个随机双盲多中心的试验研究了本品和强的松、环孢素A结合应用对移植器官排挤反响的平安性和有效性,此中肾移植试验3个和成人肝移植试验1个。一个随机开放多中心的注册试验研究了本品和强的松、他克莫司合用预防肝移植器官排挤反响的平安性和有效性。

肾脏移植

3个试验中比力了2个剂量(每次1g,每日2次和每次1.5g,每日2次)的口服本品与硫唑嘌呤对预防急性排挤事务的感化,均与环孢素A和强的松结合应用。此中1个试验应用抗胸腺球卵白治疗。那些试验在差别的单元停止,1个包罗美国的14个研究单元,1个包罗了欧洲的20个研究单元,1个包罗欧洲、加拿大和澳大利亚的21个研究单元。

次要的疗效目标是移植后最后6月内治疗失败的每个治疗组的患者比例,治疗失败定义为活检证明的急性排挤反响、发作灭亡、移植失败或无活检证明排挤反响但因其他任何原因提早中断研究的情况。本品与抗胸腺球卵白治疗(1个试验)和环孢素A/强的松(所有3个试验)结合计划与下列治疗计划停止了比力:1. 抗胸腺球卵白/硫唑嘌呤/环孢素A/强的松,2. 硫唑嘌呤/环孢素A/强的松,3. 环孢素A/强的松。

本品和环孢素A/强的松结合计划能降低移植后最后6个月内的治疗失败的发作率。下表总结了那些试验的成果。那些表格显示了治疗失败患者的比例,活检证明的发作急性排挤反响患者的比例,除灭亡和移植失败且无活检证明排挤反响外的因为其他任何原因提早中断研究的患者比例。提早中断研究的患者要随访灭亡和移植失败情况,累积灭亡和移植失败发作率零丁总结。提早中断研究的患者不随访末行研究后的排挤反响的发作情况。本品治疗组除灭亡和移植失败且无活检证明排挤反响外的因为其他任何原因提早中断研究的患者比例高于对照组,在本品3 g/d组更高。因而急性排挤反响的比例可能会被低估,尤其在本品3 g/d组。

肾脏移植试验治疗失败的发作率

(活检证明的排挤反响或因其他任何原因早期中断研究)

美国试验a

(n=499)

吗替麦考酚酯

2 g/d

(n=167)

吗替麦考酚酯

3 g/d

(n=166)

硫唑嘌呤

1~2 mg/kg/d

(n=166)

所有治疗失败

31.1%

31.3%

47.6%

无急性排挤反响的早期中断研究b

9.6%

12.7%

6.0%

活检证明的排挤反响

19.8%

17.5%

38.0%

欧洲/加拿大/澳大利亚试验c

(n=503)

吗替麦考酚酯

2 g/d

(n=173)

吗替麦考酚酯

3 g/d

(n=164)

硫唑嘌呤

100~150 mg /d (n=166)

所有治疗失败

38.2%

34.8%

50.0%

无急性排挤反响的早期中断研究

13.9%

15.2%

10.2%

活检证明的排挤反响

19.7%

15.9%

35.5%

欧洲试验d

(n=491)

吗替麦考酚酯

2 g/d

(n=165)

吗替麦考酚酯

3 g/d

(n=160)

慰藉剂

(n=166)

所有治疗失败

30.3%

38.8%

56.0%

无急性排挤反响的早期中断研究

11.5%

22.5%

7.2%

活检证明的排挤反响

17.0%

13.8%

46.4%

a 抗胸腺球卵白/吗替麦考酚酯或硫唑嘌呤/环孢素A/强的松

b 不包罗因灭亡或移植失败而早期末行研究的病例

c 吗替麦考酚酯或硫唑嘌呤/环孢素A/强的松

d 吗替麦考酚酯或慰藉剂/环孢素A/强的松

12月时累积移动物丧失或灭亡发作率总结如下:尚未发现本品治疗在移植失败或患者灭亡方面的优势。在数据上,3个试验均表白本品2 g/d或3 g/d治疗组的患者临床成果好于对照组,3个试验中的2个表白本品2 g/d治疗组的患者临床成果好于3 g/d治疗组。所有治疗组中提早末行本品治疗的患者在移动物丧失和1年灭亡率方面均较差。

肾脏移植试验

累积移动物丧失和12月时患者灭亡率

试验

吗替麦考酚酯

2 g/d

吗替麦考酚酯

3 g/d

硫唑嘌呤

或慰藉剂

美国

8.5%

11.5%

12.2%

欧洲/加拿大/澳大利亚

11.7%

11.0%

13.6%

欧洲

8.5%

10.0%

11.5%

儿童

一项开放的平安性和药代动力学研究在美国(9个中心)、欧洲(5个中心)和澳大利亚(1个中心)完成,100例儿童(3月~18岁)服用吗替麦考酚酯口服混悬液每次600 mg/ m2 ,每日2次(更大至每次1g,每日2次)和环孢素A/强的松预防肾脏的同种异体肾移植的排挤反响。儿童患者可很好耐受吗替麦考酚酯(见【不良反响】),药代动力学方面与成生齿服吗替麦考酚酯胶囊每次1g,每日2次相类似(见【药代动力学】)。各年龄组(3月~6岁、6~12岁和12~18岁组)的活检证明的排挤反响相类似。6月时总的活检证明的排挤反响比例与成人相类似。移植后12月时移动物丧失(5%)或灭亡发作率(2%)与成人肾脏移植受者类似。

肝脏移植

一项关于肝脏移植受者的双盲随机平行对照的多中心试验在美国的16个中心、加拿大的2个中心、欧洲的4个中心和澳大利亚的1个中心完成。总共入组565例患者。按照试验计划,患者先承受静脉本品每次1g,每日2次至14天,然后承受口服本品每次1.5g,每日2次,或先承受静脉硫唑嘌呤1~2 mg/kg/d,然后口服硫唑嘌呤1~2 mg/kg/d,同时结合应用环孢素A/强的松做为维持性免疫按捺治疗,现实上试验中最后口服硫唑嘌呤的中位值是1.5 mg/kg/d(范畴为0.3~3.8 mg/kg/d),1年时的口服硫唑嘌呤的中位值是1.26 mg/kg/d(范畴为0.3~3.8 mg/kg/d)。两个次要的疗效目标是:1. 移植后最后的6月内有一次或屡次活检证明并需要治疗的排挤反响、灭亡或再次移植的患者比例;2. 移植后最后12月内移植失败的患者比例患者比例患者比例患者比例患者比例患者比例

成果: 在ITT人群,与环孢素A/强的松结合应用,本品较硫唑嘌呤更能降低6个月内的急性排挤反响发作率,而1年时的灭亡和再移植的发作率类似。

6个月内的排挤反响/12月内的灭亡或再次移植

硫唑嘌呤

N=287

吗替麦考酚酯

N=278

6月内活检证明需要治疗的移植反响(包罗灭亡和再移植)

137(47.7%)

107(38.5%)

1年时灭亡和再移植

42(14.6%)

41(14.7%)

一项关于肝脏移植受者的随机、多中心、开放注册试验在中国的9个中心完成。总共入组64例均匀年龄46岁的良性末末期肝病承受初次肝移植的患者。按照伯明翰大学外科130名肝移植病人临床承受两种差别的免疫按捺计划(本品+低剂量他克莫司+糖皮量激素和他克莫司+糖皮量激素)的回忆性研究(论证了以他克莫司为根底计划增加本品能明显削减同种异体肝移植急性排挤反响的发作率:本品+低剂量他克莫司+糖皮量激素组:26.0%,他克莫司+糖皮量激素组:45.0%,而且能明显削减他克莫司的剂量,以及能削减肾毒性的发作)的根底上,设想本试验计划,治疗组患者31例承受本品片剂0.5~1.0 g,每日2次,同时结合应用他克莫司/强的松做为维持性免疫按捺治疗(剂量的选择,根据中国人群的临床要求);对照组患者33例结合应用他克莫司/强的松做为维持性免疫按捺治疗。两个次要的疗效目标是:1. 评价以他克莫司为根底计划增加本品(0.5~1.0 g,每日2次,空腹,口服至12周)预防急性排挤的疗效;2. 察看肝移植后12周内急性排挤反响的发作率、水平。两个次要的疗效目标是:1. 急性排挤反响中利用OKT3、ATG、ALG治疗的患者人数;2. 在研究过程中活检证明为急性排挤反响的次数。在12周研究过程中呈现的急性排挤反响数5例,占9.6%,均经活检证明,此中治疗组1例,属轻度急排,占3.6%,对照组4例,2例属轻度急排,1例中度急排,1例重度急排,占16.7%。5例急排中4例在甲基强的松龙冲击,1例在增大他克莫司剂量的治疗后得到缓解或控造。

成果:1. 本品对肝移植术后急性排挤反响的预防有效:整个试验入选64例患者,呈现的急性排挤反响数5例,对照组的急排发作率是治疗组的4.6倍。2. 本品没有明显的肝、肾毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高毒性:在不良事务中,转氨酶升高

狼疮性肾炎研究:

吗替麦考酚酯片在国外停止的研究-全球多中心ALMS 随机开放性试验。那是一项前瞻性随机对照全球多中心研究,纳入患者共来自20个国度88个中心。该研究为2阶段设想,别离评估吗替麦考酚酯在狼疮性肾炎的诱导期和维持期治疗的疗效与平安性。

1.诱导期研究

24周诱导期治疗纳入370例按照国际肾脏病学会/肾脏病理学会分类诊断(ISN/RPS)III、IV或V型狼疮性肾炎患者,所有患者被随机分配承受MMF口服片剂(目的剂量3g/日)或环磷酰胺(CTX)静脉输注(0.5-1.0g/m2)每月一次共给药6个月,每组各185例受试者。两组患者均合并利用波尼松口服片剂,泼尼松起始剂量0.75-1.0mg/kg/天(更大60mg/天),可按照患者病情逐步削减泼尼松剂量,研究显示两组激素用量无显著统计学差别。次要有效性起点是预先定义的尿卵白/肌酐比值降低和血清肌酐到达不变程度或呈现改善。次要起点包罗肾脏完全缓解、全身疾病活动性和损害以及平安性。

疗效成果

两组间的缓解率无显著统计学差别,MMF组共104例(56.2%)患者治疗后到达缓解,CTX组中共98例(53.0%)患者治疗后到达缓解。两组间的次要起点目标均无显著统计学差别。两组间差别病理类型狼疮性肾炎患者的缓解率未呈现显著统计学差别。

2. 维持期研究

在ALMS研究的维持治疗期内,共227例经MMF诱导治疗后到达缓解的患者被随机分配承受维持治疗,116例患者承受MMF口服片剂(目的剂量2.0g/日);111例患者承受硫唑嘌呤(AZA)口服胶囊剂(2.0 mg/kg/日)。最末,MMF治疗组和AZA治疗组的均匀(±(±(±(±(±(±(±(±(±(±(±(±(±(±(±(±(±(±(±(±(±(±(±(±(±(±

疗效成果

在次要起点至治疗失败时间方面(风险比为0.44;95%置信区间,0.25-0.77;p= 0.003)以及至肾病复发时间和至弥补治疗时间方面(风险比<1.00;p<0.05),MMF治疗组优于AZA治疗组。MMF治疗组和AZA治疗组中察看到的治疗失败发作率别离为16.4%(19/116例患者)和32.4%(36/111例患者)。

【药理毒理】

药理感化

吗替麦考酚酯(简称MMF)是麦考酚酸(MPA)的2-乙基酯类衍生物。MPA是高效、选择性、非合作性、可逆性的次黄嘌呤单核苷酸脱氢酶(IMPDH)按捺剂,可按捺鸟嘌呤核苷酸的典范合成路子,按捺有丝团结原和同种特异性刺激物引起的T和B淋巴细胞增殖,还可按捺B淋巴细胞产生抗体,按捺淋巴细胞和单核细胞糖卵白的糖基化,因而可按捺白细胞进入炎症和移动物排挤反响的部位。已经确定的两种IMPDH异构酶,即大大都已知细胞(包罗人静息淋巴细胞)中存在的异构体I,以及高度且次要表达于人活化B和T淋巴细胞中的异构体II。MPA对异构体II按捺的敏感性几乎是异构体I的五倍。吗替麦考酚酯不克不及按捺外周血单核细胞活化的早期反响,如白介素-1和白介素-2的产生等,但能够按捺那些早期反响所招致的DNA合成和增殖反响。

MPA除了按捺IMPDH,进而招致淋巴细胞削减外,还可影响淋巴细胞代谢法式化的细胞查抄点。关于人CD4+ T 细胞的研究显示,MPA能够将淋巴细胞的转录活性从增殖形态转为与代谢和存活相关的合成代谢过程,从而使T细胞处于免疫无能形态,进一步招致细胞对其特异性抗原无应答。

毒理研究

遗传毒性:

吗替麦考酚酯小鼠淋巴瘤/胸腺嘧啶激酶试验和小鼠体内微核试验成果阳性,微生物突变阐发、酵母菌基因转化阐发和中国仓鼠卵巢细胞染色体畸变试验成果阴性。变阐发、酵母菌基因转化阐发和中国仓鼠卵巢细胞染色体畸变试验成果阴性。

生殖毒性:

吗替麦考酚酯在20mg/kg/d时对雄性大鼠的生育力未见明显影响,按照体外表积推算,为临床保举用于肾脏移植剂量的0.1倍,心脏移植剂量的0.07倍。在雌性大鼠的生殖和生育试验,吗替麦考酚酯剂量为4.5mg/kg/d时未见母鼠呈现毒性反响,F1代可见畸形(次要为头和眼),为临床保举用于肾脏移植剂量的0.02倍,心脏移植剂量的0.01倍。未见对F1代或后代生育力的明显影响。

致癌性:

小鼠经口赐与吗替麦考酚酯104周,剂量达180mg/kg/日,未见致癌性,为临床保举用于肾脏移植剂量(2g/d)的0.5倍,心脏移植剂量(3g/d)的0.3倍。大鼠经口赐与104周,剂量达15mg/kg/日,未见致癌性,为临床保举用于肾脏移植剂量的0.08倍,心脏移植剂量的0.05倍。

【药代动力学】

口服或静脉给药后,吗替麦考酚酯敏捷并完全代谢为活性代谢产品MPA。药物口服吸收敏捷和根本完全吸收。MPA代谢为酚化葡萄糖醛麦考酚酸(MPAG)的形式,后者无药理活性。原药吗替麦考酚酯在静脉打针的过程中在身体中能够检测到,打针停行或口服后很短时间(大约5分钟)吗替麦考酚酯的浓度低于可定量的下限(0.4 μg/ml)。

吸收:在12例安康意愿者中口服吗替麦考酚酯的均匀绝对生物操纵度相当于静注的94%(按照MPA的AUC)。在肾移植受者中屡次给药至每天3 g时,MPA血浆浓度时间曲线下面积(AUC)表示为与剂量成比例的增高(见下述药代动力学参数表)。

在肾移植受者每天用药每次1.5g,每日2次时,食物(27克脂肪,650大卡热量)对吸收的水平无影响(按照MPA的AUC)。但食物使MPA的Cmax降低40%(见【用法用量】)。

散布:在12例安康意愿者中静脉打针和口服的MPA的均匀(±尺度差)表不雅散布容积别离为3.6(±1.5)和4.0(±1.2)L/kg。在与临床响应的浓度,97%的MPA与血浆白卵白连系。该数值取决于肾脏功用;起头治疗后白卵白连系情况发作变革可解释MPA药代动力学的非平稳性。在不变期肾移植受者中MPAG一般浓度下,82%的MPAG与血浆白卵白连系;但MPAG的浓度升高时(见于肾损害和肾移植术后移动物功用延迟的患者),因为MPAG和MPA合作与白卵白连系,MPA与白卵白的连系下降。血和血浆的放射性浓度的均匀比值约为0.6,申明了MPA和MPAG没有普遍散布到血液的细胞成分。

在体外研究中评价了其他试剂对MPA与血清白卵白或血浆卵白连系的影响,水杨酸(在血清白卵白中25 mg/dL时)和MPAG(在血浆卵白中≥460 μg/mL时)能够增加游离MPA的比例。在超越临床中能碰到的浓度时,环孢素A、地高辛、萘普生、强的松、心得安、免疫按捺剂、茶碱、甲苯磺丁脲和华法令均不增加游离MPA的比例。MPA的浓度高达100 μg/mL时对华法令、地高辛和心得安与卵白连系无影响,但使茶碱的连系由53%降低到45%,使苯妥英钠的连系由90%降低到87%。

代谢:口服或静脉给药后吗替麦考酚酯完全代谢为活性产品MPA。口服给药后在全身吸收前就代谢为MPA。MPA次要通过葡萄糖醛酸转化酶构成酚化葡萄糖醛麦考酚酸(MPAG),后者无药理学活性。在体内,MPAG通过肝肠轮回被转化成MPA。在安康意愿者口服吗替麦考酚酯后尿中也可检测到下列2-羟基乙基吗啉成分:N-(2-羧基乙基)-吗啉、N-(2-羟基乙基)-吗啉和N端氧化的N-(2-羟基乙基)-吗啉。

在服药后6~12小时后可察看到血浆MPA浓度的第二个峰值。同时服用消胆胺(4 g,每日3次),能够使MPA的AUC大约降低40%(次要降低了AUC曲线的末末部门的药物浓度)。那个现象提醒了肝肠轮回进步了MPA的血浆浓度。

肾损害患者的吗替麦考酚酯的代谢物血浆浓度升高,MPA进步50%和MPAG进步3到6倍。

肃清:只要少量以MPA形式从尿液中排出(不敷剂量的1%,可忽略)。口服放射标识表记标帜的吗替麦考酚酯后,原有放射剂量能够完全收受接管,服用剂量的93%在尿中收受接管,6%在粪便中收受接管。大大都(约87%)药量以MPAG的形式从尿液中排出。在临床应用的浓度下,MPA和MPAG凡是不克不及通过血液透析肃清。但是MPAG的血浆浓度升高(>100 μg/mL)时少量MPAG可通过血液透析肃清。胆酸连系剂,如消胆胺,通过影响药物的肝肠轮回能够降低MPA的曲线下面积(见【药物过量】)。

MPA的半衰期和血浆肃清率的均匀值(±尺度差)在口服给药别离为17.9(±6.5)小时和193(±48)mL/min,在静脉给药别离为16.6(±5.8)小时和177(±31)mL/min。

安康意愿者、肾脏移植和肝脏移植受者的药代动力学:下面用均匀值(±尺度差)来表白MPA的药代动力学参数,包罗安康意愿者吗替麦考酚酯一次给药的参数和肾脏移植和肝脏移植受者屡次给药的参数。肾脏移植和肝脏移植受者在移植后的早期(移植后40天内)较移植后晚期(移植后3~6月)的MPA AUC大约低20~41%,均匀Cmax低32~44%。

在肾脏移植受者刚移植后静脉赐与吗替麦考酚酯(每次1g,2小时输完,每日2次,连用5天)的MPA AUC较口服同样剂量者高约24%。在肝脏移植受者中静脉赐与吗替麦考酚酯每次1g,每日2次,随后赐与口服每次1.5g,每日2次的MPA AUC的均匀值与肾脏移植后赐与每次1g,每日2次类似。

安康意愿者(单次剂量)、肾脏移植和肝脏移植受者(屡次给药)

赐与吗替麦考酚酯后的药代动力学参数

给药计划

剂量和路子

Tmax

(h)

Cmax

(μg/mL)

总AUC

(μg·h/mL)

安康意愿者

(单次给药)

1g/口服

0.80

(±0.36)

(n=129)

24.5

(±9.5)

(n=129)

63.9

(±16.2)

(n=117)

肾脏移植受者

(每天二次给药)移植后时间

剂量和路子

Tmax(h)

Cmax(μg/mL)

二次剂量间期的AUC(0~12h)(μg·h/mL)

5天

1g/静脉

1.58

(±0.46)

(n=31)

12.0

(±3.82)

(n=31)

40.8

(±11.4)

(n=31)

6天

1g/口服

1.33

(±1.05)

(n=31)

10.7

(±4.83)

(n=31)

32.9

(±15.0)

(n=31)

早期(40天内)

1g/口服

1.31

(±0.76)

(n=25)

8.16

(±4.50)

(n=25)

27.3

(±10.9)

(n=25)

早期(40天内)

1.5g/口服

1.21

(±0.81)

(n=27)

13.5

(±8.18)

(n=27)

38.4

(±15.4)

(n=27)

晚期(>3月)

1.5g/口服

0.90

(±0.24)

(n=23)

24.1

(±12.1)

(n=23)

65.3

(±35.4)

(n=23)

肝脏移植受者

(每天二次给

剂量和路子

Tmax(h)

Cmax(μg/mL)

二次剂量间期的AUC(0~12h)((((

药)移植后时间

4~9天

1g/静脉

1.50

(±0.517)

(n=22)

17.0

(±12.7)

(n=22)

34.0

(±17.4)

(n=22)

早期(5~8天)

1.5g/口服

1.15

(±0.432)

(n=20)

13.1

(±6.76)

(n=20)

29.2

(±11.9)

(n=20)

晚期(>6月)

1.5g/口服

1.54

(±0.51)

(n=6)

19.3

(±11.7)

(n=6)

49.3

(±14.8)

(n=6)

AUC(0~12h)的数值是从4小时取样的数据中揣度得到的,2片500 mg的片剂与4片250 mg的片剂生物等效。

据国外文献报导,已经在狼疮性肾炎患者中,对吗替麦考酚酯的药代动力学停止了研究。狼疮性肾炎患者中的MPA药代动力学特征与在移植患者中陈述的类似(包罗所察看到的活性药物表露量的高度变异性),但因为不成预测的肾功用变革,狼疮性肾炎患者的药代动力学特征较复杂。

特殊人群的药代动力学:下面用均匀值(±尺度差)来表白在肾损害或肝损害的非移植受者单次口服吗替麦考酚酯的MPA的药代动力学参数。

肾损害

(患者例数)

剂量

Tmax

(h)

Cmax

(μg/mL)

AUC(0~96h)(μg·h/mL)

安康意愿者

GFR>80mL/min/1.73m2

(n=6)

1g

0.75

(±0.27)

25.3

(±7.99)

45.0

(±22.6)

轻度肾损害

GFR50~80mL/min/1.73m2

(n=6)

1g

0.75

(±0.27)

26.0

(±3.82)

59.9

(±12.9)

中度肾损害

GFR25~49mL/min/1.73m2

(n=6)

1g

0.75

(±0.27)

19.0

(±13.2)

52.9

(±25.5)

重度肾损害

GFR<25mL/min/1.73m2

(n=7)

1g

1.00

(±0.41)

16.3

(±10.8)

78.6

(±46.4)

肝损害

(患者例数)

剂量

Tmax(h)

Cmax

(μg/mL)

AUC(0~48h)(μg·h/mL)

安康意愿者

(n=6)

1g

0.63

(±0.14)

24.3

(±5.73)

29.0

(±5.78)

酒精性肝纤维化

(n=18)

1g

0.85

(±0.58)

22.4

(±10.1)

29.8

(±10.7)

肾损害的患者

在一个单剂研究中(每组6人),重度慢性肾脏损害的意愿受试者(肾小球滤过率(GFR)小于25ml/min/1.73m2)的血浆MPA的AUC比一般安康意愿者及轻度肾损害的意愿者(GFR>80mL/min/1.73m2)高28~75%。并且单次服用后重度肾损害的意愿受试者MPAG的AUC比一般安康意愿者高3~6倍,那与我们已知的MPAG由肾脏消弭一致。MPAG持久增高的平安性尚无数据。

重度慢性肾脏损害者(GFR小于25ml/min/1.73m2)单次静脉给药1 g的血浆MPA AUC为62.4(±19.3)μg·h/mL(n=4)。对重度慢性肾脏损害患者,多剂量吗替麦考酚酯的代谢情况尚未研究(见【留意事项】和【用法用量】)。伴重度肾损害的狼疮性肾炎患者研究数据有限,建议对GFR <30 mL/min的狼疮性肾炎患者停止治疗药物浓度监测。

肾移植术后移动物功用延迟的患者均匀MPA的AUC(0~12h)与那些移动物功用一般的术后患者相类似。在呈现移动物功用延迟的患者中有可能呈现短暂的血浆MPA游离比例增高或浓度升高,但在呈现移动物功用延迟的患者中其实不需要停止剂量调整。肾移植术后移动物功用延迟的患者均匀MPAG的AUC(0~12h)与那些移动物功用一般的术后患者比拟高2~3倍(见【留意事项】和【用法用量】)。

在8例肾移植后原发性移动物无功用的患者中,28天屡次给药后血浆MPAG的浓度累积到6~8倍,MPA的浓度累积到1~2倍。

吗替麦考酚酯的药代动力学其实不因血液透析而改动。血液透析凡是不克不及肃清MPA和MPAG。但是MPAG的血浆浓度升高(>100μg/mL)时少量MPAG可通过血液透析。

肝损害患者

18例酒精性肝硬化和6例安康意愿者参与了单次剂量(1g 口服)的研究,成果表白安康意愿者和酒精性肝硬化者的药代动力学参数类似,提醒了肝脏对MPA的葡萄糖醛酸化过程相对不受肝本色疾病的影响。但是要留意到不知因何原因本试验中安康意愿者的AUC较其他试验的安康意愿者低50%,如许使安康意愿者和酒精性肝硬化者之间很难比力。其他原因的肝脏疾病如原发胆汁性肝硬化可能产生差别效果。6例因酒精性肝硬化而重度肝损害(氨基比林呼吸尝试小于剂量的0.2%)患者赐与单次剂量(1 g 静脉给药),MMF能够敏捷转换为MPA。MPA AUC为44.1(±15.5)μg·h/mL。

儿童(年龄≤18岁)

在同种异体移植后承受了吗替麦考酚酯口服每次600mg/m2,每日2次治疗的55例儿童(1~18岁)中评价了MPA和MPAG的药代动力学参数。MPA的药代动力学参数见下表。

差别年龄和同种异体移植后差别时间的MPA的药代动力学参数(均匀值±尺度差)

年龄(例数)

时间

峰值时间

(h)

剂量校正后a的Cmax(μg/mL)

剂量校正后a的AUC(0~12h)(μg·h/mL)

1~2岁(6)d

1~6岁(17)

6~12岁(16)

12~18岁(21)

早期(7天)

3.03(4.70)

1.63(2.85)

0.94(0.546)

1.16(0.830)

10.3(5.80)

13.2(7.16)

13.1(6.30)

11.7(10.7)

22.5(6.66)

27.4(9.54)

33.2(12.1)

26.3(9.14)b

1~2岁(4)d

1~6岁(15)

6~12岁(14)

12~18岁(17)

晚期(3月)

0.725(0.276)

0.989(0.511)

1.21(0.532)

0.978(0.484)

23.8(13.4)

22.7(10.1)

27.8(14.3)

17.9(9.57)

47.4(14.7)

49.7(18.2)

61.9(19.6)

53.6(20.3)c

1~2岁(4)d

1~6岁(12)

6~12岁(11)

12~18岁(14)

晚期(9月)

0.604(0.208)

0.869(0.479)

1.12(0.462)

1.09(0.518)

25.6(4.25)

30.4(9.16)

29.2(12.6)

18.1(7.29)

55.8(11.6)

61.0(10.7)

66.8(21.2)

56.7(14.0)

a 剂量调整为相当于600 mg/m2

b n=20

c n=16

d 一个亚组为1~6岁

儿童服用吗替麦考酚酯混悬液每次600mg/m2,每日2次(更大每次1g,每日2次)的均匀MPA AUC值与成人肾移植后早期服用吗替麦考酚酯胶囊每次1g,每日2次类似。数据的变异率很大。在成人中察看到移植后早期的MPA AUC 值是移植后晚期(>3月)的45%~53%。在1~18岁间的儿童,移植后早期和晚期的MPA AUC值类似。

目前尚未开展骁悉在儿童狼疮性肾炎患者中的药物代谢动力学研究。

性别

从几个试验的数据汇总来察看MPA的药代动力学有无不同(剂量调整为相当于1 g/m2)。男性和女性的MPA AUC(1~12h)值别离为32.0±14.5(n=79)和36.5±18.8 μg·h/mL(n=4);男性和女性的MPA Cmax别离为9.96±6.19和10.6±5.64 μg/mL。差别无临床意义。

白果

与年轻移植受者比拟,尚未发现老年移植受者的吗替麦考酚酯及其代谢物的药代动力学发作变革。

【储藏】

本品应在15~30℃枯燥处保留。

【包拆】

铝塑包拆

40粒/盒

100粒/盒

【有效期】

36个月

【施行尺度】

YBH07332021

【批准文号】

国药准字H20031240

【上市答应持有人】

名称:上海罗氏造药有限公司

注册地址:中国(上海)自在商业试验区龙东大道1100号

网址:首页

【消费企业】

企业名称:上海罗氏造药有限公司

消费地址:上海市浦东新区龙东大道1100号

骁悉.与 CellCept.为瑞士巴塞尔豪夫迈·罗氏有限公司的注册商标

因为申明书更新较快,如需参阅最新批准的中文申明书,请拜候罗氏中国网站:首页

先看文献

The Anti-Inflammatory Drug Leflunomide Is an Agonist of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (抗炎药来氟米特是芳烃受体的冲动剂)| PLOS ONE[7]The Anti-Inflammatory Drug Leflunomide Is an Agonist of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor

Edmond F. ODonnell,Katerine S. Saili,Daniel C. Koch,Prasad R. Kopparapu,David Farrer,William H. Bisson,Lijoy K. Mathew,Sumitra Sengupta,Nancy I. Kerkvliet,Robert L. Tanguay,Siva Kumar Kolluri Published: October 1, 2010 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013128ArticleAuthorsMetricsCommentsMedia CoverageReader CommentsFiguresFigures

Published: October 1, 2010 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013128ArticleAuthorsMetricsCommentsMedia CoverageReader CommentsFiguresFigures

Abstract

Background

Abstract

BackgroundThe aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is a ligand-activated transcription factor that mediates the toxicity and biological activity of dioxins and related chemicals. The AhR influences a variety of processes involved in cellular growth and differentiation, and recent studies have suggested that the AhR is a potential target for immune-mediated diseases.

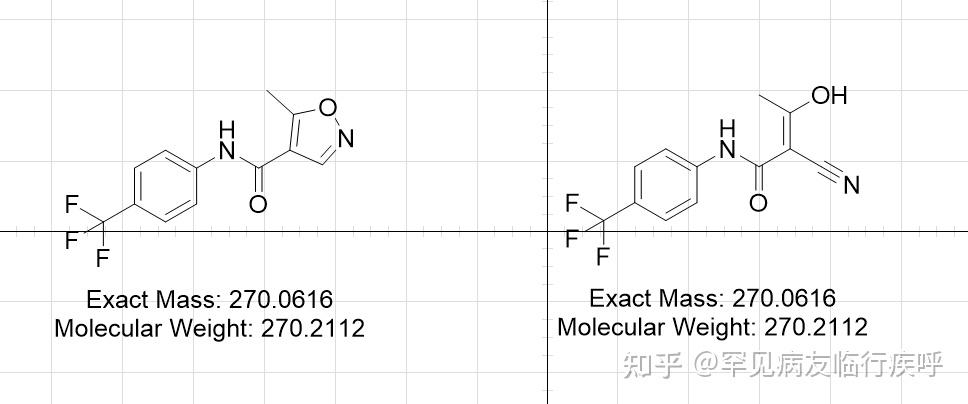

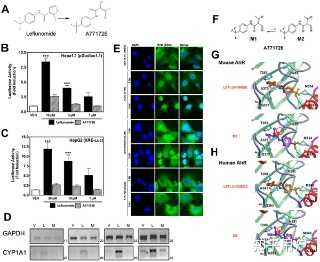

Methodology/Principal FindingsDuring a screen for molecules that activate the AhR, leflunomide, an immunomodulatory drug presently used in the clinic for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, was identified as an AhR agonist. We aimed to determine whether any biological activity of leflunomide could be attributed to a previously unappreciated interaction with the AhR. The currently established mechanism of action of leflunomide involves its metabolism to A771726, possibly by cytochrome P450 enzymes, followed by inhibition of de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis by A771726. Our results demonstrate that leflunomide, but not its metabolite A771726, caused nuclear translocation of AhR into the nucleus and increased expression of AhR-responsive reporter genes and endogenous AhR target genes in an AhR-dependent manner. In silico Molecular Docking studies employing AhR ligand binding domain revealed favorable binding energy for leflunomide, but not for A771726. Further, leflunomide, but not A771726, inhibited in vivo epimorphic regeneration in a zebrafish model of tissue regeneration in an AhR-dependent manner. However, suppression of lymphocyte proliferation by leflunomide or A771726 was not dependent on AhR.

ConclusionsThese data reveal that leflunomide, an anti-inflammatory drug, is an agonist of the AhR. Our findings link AhR activation by leflunomide to inhibition of fin regeneration in zebrafish. Identification of alternative AhR agonists is a critical step in evaluating the AhR as a therapeutic target for the treatment of immune disorders.

Citation:ODonnell EF, Saili KS, Koch DC, Kopparapu PR, Farrer D, Bisson WH, et al. (2010) The Anti-Inflammatory Drug Leflunomide Is an Agonist of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor. PLoS ONE 5(10): e13128. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013128

Editor:Fernando Rodrigues-Lima, University Paris Diderot-Paris 7, France

Received: March 17, 2010; Accepted: August 20, 2010; Published: October 1, 2010

Copyright:© 2010 ODonnell et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding:This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) grant number ES016651, the National Science Foundation grant number 0641409, and the Aquatic Biomedical Models and the Cell Imaging and Analysis Facility Cores of the Environmental Health Sciences Center, NIEHS grant number P30 ES00210. EFO, KSS, DCK and DF were supported by NIEHS training grant (T32ES07060). EFO is supported by a pre-doctoral fellowship from the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-10-1-0160), and DCK is supported by the National Research Service Award (1F31CA144571-01) from the National Cancer Institute. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests:

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

IntroductionThe aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is a member of the Per-AhR/Arnt-Sim (PAS) family of proteins. The AhR is a cytosolic transcription factor that, in its latent unliganded state, forms complexes with HSP90 and XAP2.[1] Upon ligand binding, the AhR translocates to the nucleus, where it complexes with its heterodimerization partner, the AhR Nuclear Translocator (Arnt), to modulate expression of AhR target genes containing functional xenobiotic response elements (XREs).[1] Activation of AhR by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) is associated with a number of adverse effects in animals including tumor promotion and immune suppression.[2] Studies have shown that the AhR, upon activation by TCDD, inhibits cellular proliferation by inducing expression of cell cycle inhibitor p27Kip1.[3] Interaction of the AhR with retinoblastoma protein has also been reported. [4], [5], [6] Further, the AhR has been shown to modulate cell cycle progression and cellular differentiation independent of TCDD.[7] In addition, the AhR can also modulate tissue regeneration pathways in vivo.[8], [9] The AhR can induce mitogen-activated protein kinases as well as modulate function of tyrosine kinases.[10], [11] Despite the negative physiological effects associated with TCDD activation of AhR in vivo, recent studies on the AhR suggest that this receptor may play a role in the control of tumor progression in the absence of exogenous compounds and further, that modulators of the AhR may be useful as therapeutics for immune-mediated diseases and cancer.[12], [13], [14], [15], [16]In the present study, we conducted a screen of clinically used compounds in order to identify novel AhR ligands and identified the anti-rheumatoid arthritis drug leflunomide as a putative AhR activator. Consistent with this result of our screen, Hu et al previously reported leflunomide as an AhR activator during a study evaluating the usefulness of CYP1A1 as a biomarker of AhR activation.[17] Leflunomide (Arava®) is an immunomodulatory drug whose primary mechanism of action is attributed to its metabolite A771726 via inhibition of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, which in turn disrupts pyrimidine biosynthesis and ultimately inhibits T and B cell proliferation.[18] Potent suppression of the immune response by TCDD is a well-known AhR-dependent phenomenon.[15], [19], [20] Because leflunomide is both an agonist of the AhR and a known immunosuppressive agent, we aimed to determine if the biological activity of leflunomide could be attributed to a previously unappreciated activation of the AhR. In addition, given that one of the most well known roles of the AhR is activation of drug metabolizing enzymes upon binding to xenobiotics,[1] we also investigated leflunomides ability to regulate several genes involved in phase 1 and phase 2 metabolism in an AhR-dependent manner. This investigation included CYP1A2, which has been shown previously to facilitate leflunomide conversion to A77176.[21]. Lastly, we investigated in vivo activation of the AhR and initiation of non-immune related AhR responses by leflunomide.

Materials and Methods Cell CultureMouse WT Hepa1c1c7 hepatoma cells, mouse Hepa1 B13NBii1 (C4) cells,[22] mouse vT{2} cells,[23] mouse Hil1.1c2 cells,[24] and human HepG2 hepatoma cells were cultured in DMEM with L-glutamine (Mediatech Inc., Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Tissue Culture Biologicals, Tulare, CA) in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Mouse WT Hep1c1c7 cells are hereafter referred to as WT Hepa1, while Hil1.1c2 cells are hereafter referred to as Hepa1.1 cells. Mouse Hepa1 C4 and VT{2} cells are derivatives of the WT Hepa1 cell line and were purchased from ATCC. Mouse Hepa1 C4 cells lack functional Arnt activity due to a point mutation (GLY326ASP),[25] while vT{2} cells are C4 cells engineered to stably express a full length Arnt cDNA.[23] Mouse Hepa1.1 cells,[24] were kindly provided by Dr. M.S. Dension (University of California, Davis, CA, USA). All cell lines were cultured with 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (Mediatech Inc., Manassas, VA), and were typically passaged every three days at a dilution of 1∶5. Mouse splenocytes used in ex vivo experiments were cultured in RPMI 1640 media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% FBS without antibiotics.

Chemicals and ReagentsLeflunomide and A771726 were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO) and Alexis Biochemicals (Plymouth Meeting, PA), respectively, and dissolved in DMSO. Fluvoxamine Maleate, a chemical inhibitor of CYP1A1 and CYP1A2, was purchased from Tocris Biosciences (Ellisville, MO) and dissolved in DMSO. All other chemicals, the chemical library, and reagents were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted.

Reporter Gene ConstructsThe following constructs were used for reporter gene assays. Hepa1.1 cells stably express pGudLuc1.1, an expression vector with a 484-base pair fragment of the promoter region of mouse cyp1a1 that contains four functional XRE sequences inserted directly upstream of the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) viral promoter and firefly luciferase gene.[24] For transient transfection assays in WT Hepa1, C4, vT{2}, and HepG2 cells, the XRE-MMTV-Luc expression vector was used. XRE-MMTV-Luc, hereafter referred to as XRE-Luc, contains a synthetic XRE oligonucleotide upstream of the MMTV viral promoter.[26]. The β-galactosidase expression vector, which expresses the β-galactosidase gene under control of a minimal CMV promoter (pCH 110; Pharmacia), was used for normalization of luciferase activity as described previously.[27]. PCDNA3.0 (Invitrogen) was used as carrier DNA for transfection normalization purposes. Reconstitution of Arnt activity in C4 cells was achieved by transfecting cells with an expression vector for Arnt.[28]

Reporter Gene AssaysHepa1.1 cells were plated at a density of 1×104 cells/well in 100 µL of cell culture media in 96 well plates and grown overnight. The following day, cells were treated for four hours with vehicle (DMSO), leflunomide, or A771726; the total concentration of DMSO did not exceed 0.1% v/v. Following incubation with the compounds, the media was removed and cells were harvested with 100 µL passive lysis buffer (Promega) for 15 min with mild orbital shaking. Next, 75 µL of the resulting lysates were collected and transferred to opaque 96 well plates, where they were assayed well-by-well for luciferase activity by injection of luciferase assay substrate (Promega) with a 2 sec mixing time and 15 sec integration period on a Tropix TR717 microplate luminometer. Data were expressed as fold inductions relative to vehicle (DMSO) treated cells.

For transient transfections, Hepa1, vT{2}, C4, and HepG2 cells were plated at a density of 0.75×105 cells/well in 24 well plates and grown overnight. The following day the cells were transfected with 600 ng of the XRE-Luc expression vector, 100 ng β-galactosidase expression vector, and 300 ng PCDNA3.0 as carrier DNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, CA) according to the manufacturers recommended protocol. Co-transfection with the β-galactosidase expression vector was for normalization purposes as described below. Pertaining specifically to reconstitution of Arnt activity in C4 cells, which lack functional Arnt activity, cells were co-transfected with 300 ng Arnt expression vector or with PCDNA3.0 carrier DNA, thereby keeping the total amount of DNA transfected equal among experiments.

Approximately 18 hours after transfection the media was removed and the cells were treated with DMSO, leflunomide, or A771726 for an additional 18 hours; the total concentration of DMSO in experiments did not exceed 0.1% v/v. After incubation with the compounds, cells were lysed essentially as described above for Hepa1.1 experiments, except that the total lysate volume was increased to 150 µL, the amount of lysate assayed in the luminometer was increased to 100 µL, and 10–25 µL of lysate was used for mouse and human β-galactosidase assays for transfection normalization, respectively.[29], [30], [31], [32] Briefly, β-galactosidase activity was determined by incubating a portion of the cell lysates for approximately 20 minutes with 100 µL β-galactosidase reaction buffer per well (100 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.3, 1.25 mM MgCl2, 62.5 mM 2-Mercaptoethanol, and 1.1 mg/mL O-nitrophenyl-beta-D-galactopyranoside) at 37°C, and reading the absorbance at 405 nm in a spectromax 96-well plate reader. To normalize the data in transient transfection experiments, raw luciferase values were divided by their respective β-galactosidase activity. Values are presented as fold inductions relative to vehicle treated cells. Chemical Inhibition of CYP1A2Reporter assays utilizing chemical inhibition of CYP1A2 were performed as described above for the Hepa1.1 reporter assay, with some modifications. Briefly, prior to treatment with vehicle (DMSO) or leflunomide, cells were pre-treated for 3 hours with fluvoxamine at a final concentration of 10 µM. Cells were then treated for 4 hours with vehicle or leflunomide and luciferase activity was measured as described above.

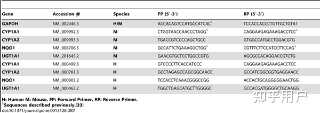

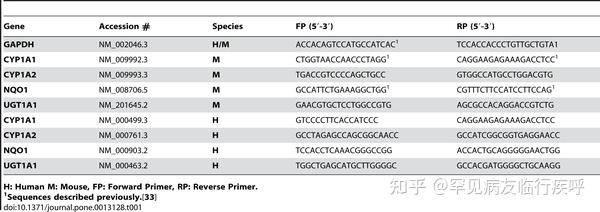

Semi-quantitative Polymerase Chain ReactionFor analysis of AhR target gene induction, Hepa1, C4, VT{2}, or HepG2 cells were plated in 6 well dishes and grown overnight such that they were 50% confluent at the time of treatment. Cells were then treated with vehicle (DMSO) and varying levels of either leflunomide or A771726 for approximately 18 hours, at which time they were harvested using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufactures recommended protocol. The concentration of RNA lysates were quantified with a nanodrop spectrophotometer and frozen at −20°C until needed. Reverse Transcriptase PCR analysis was performed using the Superscript RT III Kit with random hexamers and a 1 µg RNA Input (Invitrogen, CA). Semi-quantitative Real Time PCR was performed following cDNA synthesis exactly as previously described.[33] Primers were designed to amplify Cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1), Cytochrome P450 1A2 (CYP1A2), UDP glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1), NAD(P)H dehydrogenase [quinone 1] (NQO1), and Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), which was used as a control for equal loading. The sequences, accession numbers, and species specificity for the primers used in this study are shown in Table 1. Aliquots of individual PCR reactions at non-saturating PCR conditions were removed at various cycle numbers (indicated in figures) and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis on 2.0% TAE gels. Gels were visualized with ethidium bromide using a GeneGenius digital imaging system (Syngene).

Table 1 Primer sequences for RT-PCR experiments.GeneAccession #SpeciesFP (5′-3′)RP (5′-3′)GAPDHNM_002046.3H/MACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC 1TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA1CYP1A1NM_009992.3MCTGGTAACCAACCCTAGG 1CAGGAAGAGAAAGACCTCC 1CYP1A2NM_009993.3MTGACCGTCCCCAGCTGCCGTGGCCATGCCTGGACGTGNQO1NM_008706.5MGCCATTCTGAAAGGCTGG 1CGTTTCTTCCATCCTTCCAG 1UGT1A1NM_201645.2MGAACGTGCTCCTGGCCGTGAGCGCCACAGGACCGTCTGCYP1A1NM_000499.3HGTCCCCTTCACCATCCCCAGGAAGAGAAAGACCTCCCYP1A2NM_000761.3HGCCTAGAGCCAGCGGCAACCGCCATCGGCGGTGAGGAACCNQO1NM_000903.2HTCCACCTCAAACGGGCCGGACCACTGCAGGGGGAACTGGUGT1A1NM_000463.2HTGGCTGAGCATGCTTGGGGCGCCACGATGGGGCTGCAAGGOpen in a separate window

H: Human M: Mouse, FP: Forward Primer, RP: Reverse Primer.

1 Sequences described previously. <a href="http://europepmc.org/article/PMC/2948512#pone.0013128-Bisson1">[33] Table 1. Primer sequences for RT-PCR experiments.

Table 1. Primer sequences for RT-PCR experiments.Download:

PPTPowerPoint slidePNGlarger imageTIFForiginal imagehttps://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013128.t001 ImmunofluorescenceWT Hepa1 cells (1×104 cells/well) were plated in 8-well chamber slides and grown overnight. The following day, cells were treated with the indicated compounds for either 1 or 3 hours. At the end of the treatment, cells were processed for immunofluorescence analysis as described previously.[29], [30], [31], [32], [33] Briefly, cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde, followed by a 10-minute incubation with 0.1% Triton X-100. After fixing, cells were blocked (1% w/v BSA Fraction V) for 1 hour at room temperature (RT). Primary staining was then performed using an AhR antibody (Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA) diluted 1∶800 dilution in blocking medium for 3 hours at RT. After extensive washing with PBS, cells were stained with a FITC conjugated goat-anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) at a dilution of 1∶600 for 1 hour at RT. Slides were then washed with PBS three times and coverslippped with Pro-Fade staining reagent with DAPI (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen). Cells were imaged with a Zeiss Axiovert 200 inverted microscope equipped with a camera and Metamorph image capture software.

Molecular Docking StudiesLeflunomide and its metabolite A771726 were docked into a mouse and human AhR ligand binding domain (LBD) homology model using ICM software as described previously, and the binding energy was subsequently calculated.[33]

Zebrafish CareAB strain (wildtype) embryos were obtained from the Sinnhuber Aquatic Research Laboratory in the Aquatic Biomedical Models Facility Core of the Environmental Health Sciences Center, Oregon State University. Zebrafish were raised using standard protocols in compliance with Oregon State University animal care and use protocols. Embryos were incubated at 28°C for all experiments.

Zebrafish Fin Regeneration AssayThe fin regeneration assays were performed as described previously.[9] Briefly, 48 hours post fertilization (hpf) embryos were dechorionated, anesthetized with tricaine (tricaine methanesulfonate; MS-222), placed on a 1% agarose plate, and the primordial caudal fin was amputated just posterior to the notochord using a surgical blade. Embryos were allowed to recover in embryo water approximately 10 minutes followed by a 3-day exposure to vehicle, leflunomide (25 µM), or A771726 (10 µM) diluted in embryo water. Three days post amputation (dpa) embryos were evaluated for mortality, abnormal development, and fin regeneration. Photographs were collected by placing embryos on agarose plates and using a macro camera (Nikon Coolpix 5000) attached to a stereomicroscope (Nikon SMZ1500).

Zebrafish Morpholino Gene KnockdownsAntisense repression of AhR2 was performed using a translation start-site targeting morpholino oligonucluotide (MO) (Gene Tools, Philomath, OR) as described previously.[9] All MOs were diluted to 3 mM in 1× Danieaus solution (58 mM NaCl, 0.7 mM KCl, 0.4 mM MgSO4, 0.6 mM Ca(NO3)2, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.6) as described previously.[34] Next, 2 nL of the AhR2 or standard control MO (Gene Tools) solutions were microinjected into 1–2 cell stage embryos. A fluorescein tag at the 3′ end of the MOs was used to evaluate microinjection efficiency at 24 hpf. Six hpf MO-injected embryos were exposed to vehicle, leflunomide (10 µM), or A771726 (10 µM) and incubated for 3 days followed by toxicity evaluations and immunohistochemistry. A total of 48 hpf embryos were dechorionated and either directly exposed to DMSO (vehicle), leflunomide (10 µM), or A771726 (1 µM or 10 µM) diluted in embryo water or had their caudal fin amputated prior to treatment with the test compounds. Embryos were then incubated for 3 days followed by morphological evaluation and immunohistochemical staining.

Zebrafish CYP1A ImmunohistochemistryFollowing exposure to the indicated compounds, embryos were euthanized with tricaine and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde followed by immunostaining of zfCYP1A as described previously.[9] The primary monoclonal antibody used was C107 mouse anti- zfCYP1A, 1∶500 (Biosense Laboratories, Bergen, Norway). The secondary antibody used was Alexa-546 conjugated goat anti-mouse, 1∶1000 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Embryos were mounted in 50% glycerol on a glass coverslip and imaged with an Axiovert 200 M (Zeiss).

Lymphocyte Proliferation AssayC57BL/6J (B6) mice and B6.129-AhRtm1Bra/J (AhR −/−) mice (purchased from The Jackson Laboratory) were bred and maintained in our specific pathogen-free animal facility at Oregon State University. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Spleens of AhR +/+ and AhR −/− mice were removed and whole splenocyte suspensions were prepared. Cells were then labeled with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) [35] and cultured with 250 ng/mL anti-CD3 and 10 µg/mL LPS in the presence of 0, 5, 10 or 50 µM leflunomide or 10 or 50 µM A771726. After 72 hours, the cells were harvested and stained with fluorochrome-labeled antibodies to CD4 and CD8 and B220 (BD Pharmingen) for flow cytometric analysis. Subset-specific cell division was measured based on the two-fold dilution of CFSE fluorescence that occurs with each round of cell division. Flow analysis was performed using a Beckman Coulter FC500 flow cytometer and analyzed with WinList software (Verity Software House).

Statistical AnalysisReporter gene studies and leflunomide proliferation assays in AhR +/+ or AhR −/− splenocytes were analyzed by one and two-way ANOVA, respectively. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

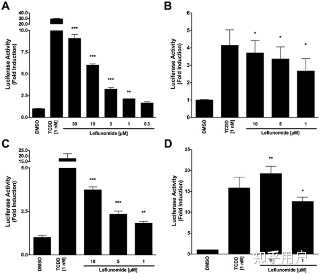

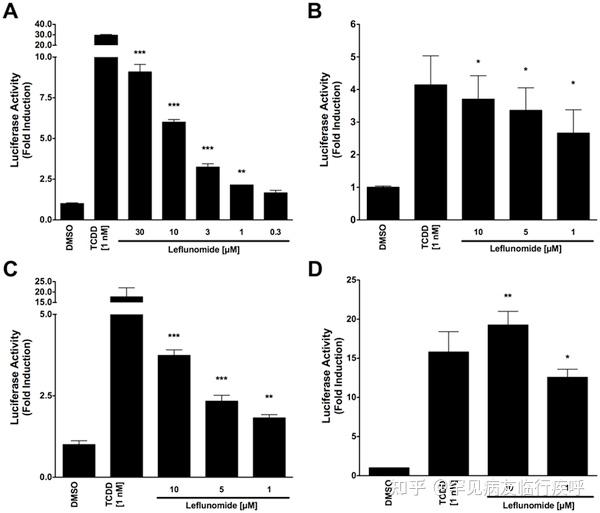

ResultsLeflunomide Induces AhR-Response Element-Containing Reporter Genes

Following the identification of leflunomide as a putative AhR ligand from our small molecule screening, we set out to further characterize the compounds ability to activate AhR transcription. To this end, we performed reporter gene assays to investigate the dose-dependent activation of the AhR by leflunomide. We first used a mouse hepatoma cell line stably expressing an AhR responsive luciferase reporter gene (Hepa1.1) [24] and found that leflunomide activated AhR transcription starting from 1 µM in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1A), which was in accordance with our screening data and other published studies.[17] To further assess leflunomide activation of the AhR, we transiently transfected human HepG2 and mouse WT Hepa1 hepatoma cells with a luciferase reporter gene expression vector under control of a promoter containing xenobiotic response elements (XRE-Luc). Consistent with our observations in Hepa1.1 cells, we observed activation of AhR-mediated transcription in both Hepa1 (Figure 1B), and HepG2 (Figure 1C) cell lines. When we transiently expressed additional levels of Arnt in HepG2 cells (Figure 1D), induction of the XRE reporter increased significantly.Figure 1. Induction of AhR-mediated reporter gene activity by leflunomide.

Figure 1. Induction of AhR-mediated reporter gene activity by leflunomide.

Figure 1. Induction of AhR-mediated reporter gene activity by leflunomide.Download:

PPTPowerPoint slidePNGlarger imageTIFForiginal image(A) Hepa1.1 cells were treated with varying doses of leflunomide ranging from 0.3 to 30 µM for 4 hours and luciferase activity was measured. Treatment with 1 nM TCDD was included as a positive control. Leflunomide strongly induced the luciferase reporter gene starting from 1 µM. (B) WT mouse Hepa1 hepatoma or human HepG2 hepatoma cells (C) were transiently transfected with an XRE-Luc reporter gene and β-galactosidase expression vector as described in the methods

section. Cells were treated with leflunomide or TCDD as indicated for 16 hours and assayed for luciferase activity; Luciferase values are normalized to β-galactosidase activity. In both WT Hepa1 and HepG2 cells, treatment with 10, 5, or 1 µM significantly increased reporter gene activity, although to a lesser extent than 1 nM TCDD. (D) HepG2 cells were co-transfected with an Arnt expression vector (300 ng) along with the XRE-Luc reporter gene (600 ng). A significant increase in the XRE reporter gene activity was observed compared to HEPG2 cells transfected with the XRE reporter construct alone. Results are the mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. *** p<0.0001, ** p<0.001, * p<0.05 as determined by ANOVA with a Newman-Keuls multiple comparison post-test.

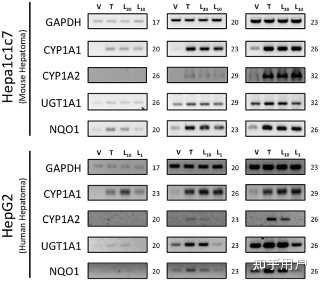

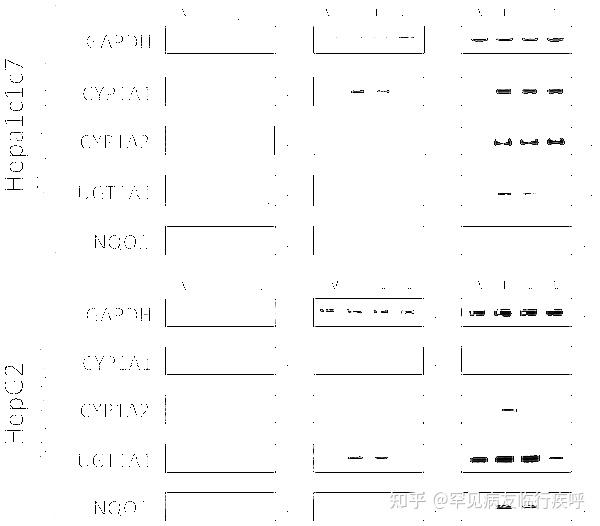

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013128.g001 Activation of AhR Target Genes by LeflunomideAfter confirming leflunomides ability to induce AhR-responsive reporter genes, we next evaluated leflunomides ability to modulate expression of several known endogenous AhR target genes by semi-quantitative PCR. First, using WT Hepa1 cells, we evaluated CYP1A1, CYP1A2, NQO1, and UGT1A1 expression with increasing concentrations of leflunomide. As shown in Figure 2A, leflunomide exposure strongly induced the transcription of CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and NQO1 similar to the maximal expression produced by 1 nM TCDD exposure. In addition, despite a significant basal expression of UGT1A1 in WT Hepa1 cells, both leflunomide and TCDD modestly upregulated UGT1A1. We also evaluated CYP1A1, CYP1A2, NQO1, and UGT1A1 expression following leflunomide exposure in HepG2 human hepatoma cells. Consistent with the results obtained from the Hepa1 cells, leflunomide activated all of the AhR target genes in a dose-dependent manner in HepG2 cells. Together, these data indicate that leflunomide increases expression of several AhR target genes involved in drug metabolism in both human and mouse cells.

Figure 2. Activation of the AhR target genes by leflunomide. Figure 2. Activation of the AhR target genes by leflunomide.

Figure 2. Activation of the AhR target genes by leflunomide.Download:[8]

PPTPowerPoint slidePNGlarger imageTIFForiginal imageHepa1 and HepG2 cells were treated with vehicle (V, 0.1% DMSO), TCDD (T, 1 nM), or leflunomide (L20, 20 µM; L10, 10 µM; L1, 1 µM) for 18 hours. RNA was isolated and semi quantitative RT-PCR was performed for the AhR target genes Cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1), Cytochrome P450 1A2 (CYP1A2), UDP glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1), and NAD(P)H dehydrogenase [quinone 1] (NQO1), as described in the methodssection. Expression analysis of GAPDH (Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) was performed as a control. Cycle numbers during which PCR reactions were sampled are indicated. PCR products were visualized on a 2% TAE agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Leflunomide activated the selected panel of AhR target genes in WT Hepa1 (A) and HepG2 cells (B).

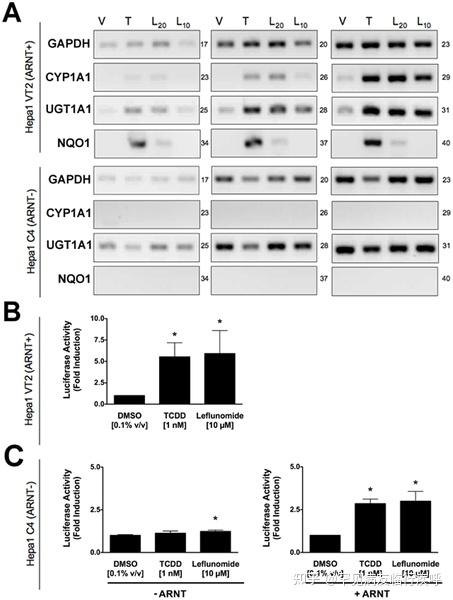

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013128.g002 Activation of AhR Target Genes by Leflunomide Requires the AhR Heterodimerization Partner ArntGiven that the structure of leflunomide differs significantly from that of the classical ligand, TCDD, we wanted to confirm that its ability to activate transcription of AhR target genes was dependent on the presence of a functional Arnt protein, which would indicate that leflunomide activates AhR signaling through the classical pathway. To this end, we used the C4 mutant cell line, which has non-functional Arnt activity (Arnt G326D) [25], and Hepa1 VT{2} cells, which have restored Arnt activity due to stable re-expression of wildtype Arnt.[23] We performed semi-quantitative PCR to evaluate target gene induction in the two Hepa1 derivative cell lines following treatment with leflunomide (Figure 3A). The AhR target genes CYP1A1, UGT1A1, and NQO1 were induced in the Arnt transcription proficient cell line following exposure to leflunomide; however, induction of NQO1 was considerably weaker. Neither CYP1A1 nor NQO1 was induced by leflunomide in the Hepa1 C4 cell line, whereas basal UGT1A1 expression was not altered. Furthermore, leflunomide activated XRE-Luc reporter gene activity in Hepa1 vT{2} cells in a dose-dependent manner, with a maximal induction comparable to that of TCDD (Figure 3B), while neither TCDD nor leflunomide increased reporter gene activity in the Arnt deficient Hepa1 C4 line (Figure 3C). To verify the results observed in vT{2} cells, C4 cells were also transiently co-transfected with an expression vector for Arnt, which rescued induction of the XRE-Luc reporter by both TCDD and leflunomide (Figure 3C).Figure 3.Activation of AhR target genes by leflunomide requires Arnt. Figure 3. Activation of AhR target genes by leflunomide requires Arnt.

Figure 3. Activation of AhR target genes by leflunomide requires Arnt.Download:[9]

PPTPowerPoint slidePNGlarger imageTIFForiginal imageFigure 3. Activation of AhR target genes by leflunomide requires Arnt.

(A) Induction of the AhR target genes CYP1A1, UGT1A1, and NQO1 was performed as in figure 2. Vehicle (V, 0.1% DMSO), TCDD (T, 1 nM), leflunomide (L20, 20 µM; L10, 10 µM). GAPDH expression was used as a control. PCR cycle numbers are indicated. Target gene induction in Hepa1 vT{2} cells expressing a functional Arnt protein was similar as to that seen with WT Hepa1 cells. CYP1A1 and NQO1 were not induced by leflunomide in Hepa1 C4 cells that do not express a functional Arnt protein. (B–C) XRE-Luc reporter gene assays in Hepa1 vT{2} and C4 cells. Cells were transfected and treated with leflunomide or controls (VEH, Vehicle, 0.1% v/v DMSO; TCDD, 1 nM; and LEF, leflunomide,10 µM) as described in the methodssection. (B) Consistent with semi quantitative RT-PCR analysis, TCDD and leflunomide induced expression of the XRE-Luc reporter gene in Hepa1 vT{2} cells. (C) Treatment with TCDD or leflunomide failed to activate the XRE-Luc reporter in the Hepa1 C4 cells. However, transient co-expression of Arnt rescued XRE-Luc reporter gene induction. Reporter gene assays are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

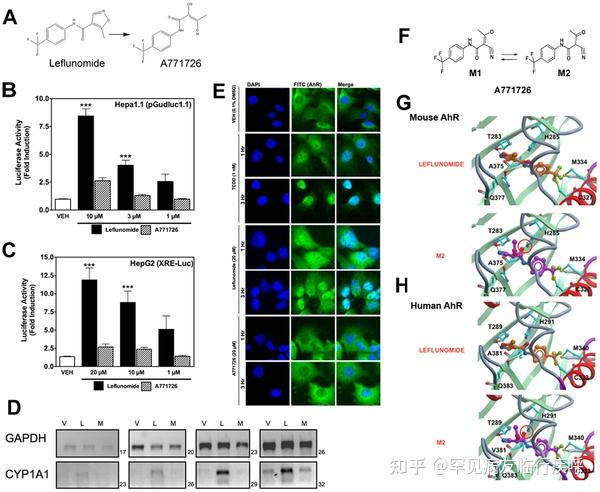

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013128.g003 Leflunomide, but not its Biologically Active Metabolite, A771726, Activates the AhRPreviously, an in vitro metabolism study on isoxazole ring scission found that leflunomide may be metabolized via a cytochrome P450-mediated isoxazole ring opening N-O bond cleavage to form its active metabolite, A771726.[21] Given the significant structural change incurred during the metabolism of leflunomide to A777176 (Figure 4A), we were interested to determine whether the metabolite could also activate the AhR. To this end, we performed reporter gene assay with both leflunomide and A771726 in Hepa1.1 cells (Figure 4B) and HepG2 cells (Figure 4C). While leflunomide activated the reporter gene in a concentration-dependent manner, A771726 failed to significantly induce the AhR-dependent reporter gene in both the cell lines. We also evaluated the induction of CYP1A1 by leflunomide and A771726 using semi-quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 4D). Consistent with the reporter gene data, A771726 failed to induce CYP1A1 expression beyond that of vehicle treatment, while leflunomide strongly induced CYP1A1 expression, consistent with earlier observations.

Figure 4.Leflunomide, but not its active metabolite, A771726, activates the AhR. Figure 4. Leflunomide, but not its active metabolite, A771726, activates the AhR.

Figure 4. Leflunomide, but not its active metabolite, A771726, activates the AhR.Download:[10]

PPTPowerPoint slidePNGlarger imageTIFForiginal imageFigure 4. Leflunomide, but not its active metabolite, A771726, activates the AhR.

(A) Structures of leflunomide (left) and its metabolite A771726 (right). (B–C) Reporter gene assays were conducted in Hepa1.1 cells or in HepG2 cells transiently transfected with XRE-Luc reporter gene. Results are the mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments, each of which consisted of at least three biological replicates. ***: p<0.001 compared with vehicle treatment and p<0.05 compared with corresponding dose of A771726. (D) To confirm the observations of the reporter gene assays, we performed semi quantitative RT-PCR in WT Hepa1 cells for CYP1A1 with total RNA isolated from cells treated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO), leflunomide (L, 20 µM) or A771726 (M, 20 µM) as described in Figure 2. GAPDH was included as a control. Consistent with reporter gene assays, A771726 failed to activate CYP1A1 beyond that of vehicle treatment, while leflunomide induced strong CYP1A1 expression. (E) Cellular localization of AhR was analyzed by immunofluorescence of Hepa1 cells treated with TCDD, leflunomide, or A771726 for 1 or 3 hours. The FITC (green) channel represents AhR staining, while DAPI (blue) represents the nucleus. The AhR translocated to the nucleus following treatment with both TCDD and leflunomide, while it remained in the cytosol following treatment with A771726. (F) M2 is the major tautomeric form of A771726. Molecular docking of M2 and leflunomide in the homology models of mouse (G) and human (H) AhR ligand binding domain reveal favorable energetic and docking for leflunomide but not M2.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013128.g004To further confirm our observation that A771726 is not an AhR agonist, we evaluated the ability of both leflunomide and A771726 to facilitate AhR translocation from the cytosol to the nucleus (Figure 4E). After treatment for 1 and 3 hours, both TCDD and leflunomide strongly promoted AhR nuclear localization, while A771726 did not. Together, these data indicate that leflunomide but not its metabolite, A771726, is a ligand of the AhR.

Molecular Docking of Leflunomide and A771726We were next interested in determining if there is a structural explanation for the observed disparity between the AhR activation by leflunomide, but not its metabolite. To this end, leflunomide and its metabolite A771726 (Figure 4A) were docked into the mouse and human AhR-LBD homology model as previously described. [33] For the primary metabolite, A771726, the most predominant tautomeric form in solution, M2 [21], was considered in the study (Figure 4F). Both compounds docked into the binding pocket, but produced distinct binding energetics. Specifically, leflunomide established two hydrogen bond (HB) interactions between the nitrogen atom of the isoxazole ring of the ligand and the OH of the side chain of Thr 289/283 and between the amide NH of the ligand and the carbonyl CO of the side chain of Gln 383/377 (Figure 4G) with a predicted binding energy of −2.65 kcal/mol (human) and −2.84 kcal/mol (mouse). Conversely, A771726 established only a single HB interaction between the nitrogen of the CN of the compound and the OH of the side chain of Thr 289/283 (Figure 4H) but with a high unfavorable (+77.5 kcal/mol (human); +40.48 kcal/mol (mouse)) binding energy. This was due to the clash in the binding pocket between the carbonyl oxygen CO of the amide group of the compound and the side chain of His 291/285 (Figure 4G). Thus, the observed AhR agonistic activity of leflunomide as well as inactivity of A771726 could be explained by in silico molecular docking.

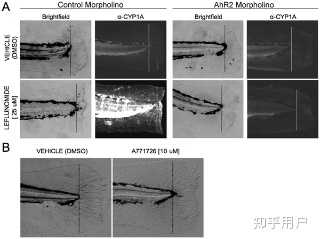

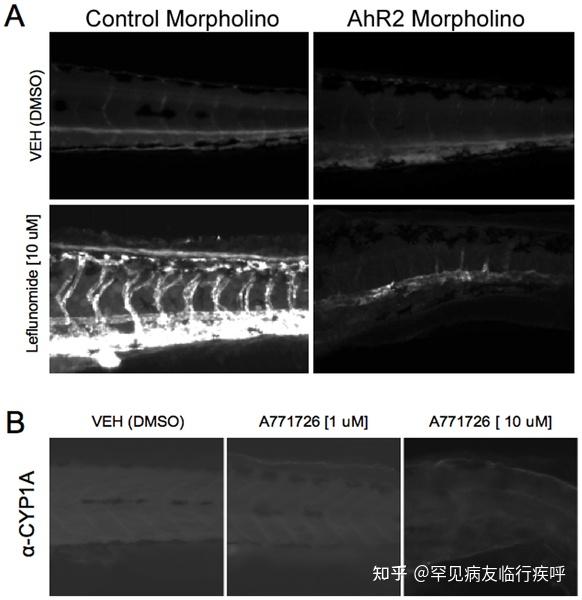

Leflunomide, but not its Active Metabolite, A771726, Induces AhR-dependent CYP1A Expression in vivoFollowing characterization of AhR activation by leflunomide in mouse and human hepatoma cells, we evaluated the functional consequences of AhR activation in vivo using the embryonic zebrafish model.[9] We first evaluated whether leflunomide exposure induced AhR target gene CYP1A in vivo. Zebrafish embryos were waterborne exposed to 10 µM leflunomide from 6 hpf to 120 hpf, after which CYP1A expression was evaluated by immunohistochemistry. In the absence of exogenous ligand, CYP1A expression was undetectable, and leflunomide exposure strongly induced CYP1A expression throughout the larval vasculature. Zebrafish have three AhR isoforms and AhR2 was shown to be the dominant isoform that regulates CYP1A in response to TCDD treatment.[8] To determine if the leflunomide-mediated CYP1A induction was AhR2-dependent, we used AhR2 morpholinos to repress AhR2 expression. While leflunomide induced strong CYP1A expression in control morphants (Figure 5A), CYP1A expression was markedly reduced in the AhR2 morphants, indicating that the induction was AhR2-dependent. However, exposure to A771726 did not increase CYP1A expression (Figure 5B). Taken together, these data indicate that leflunomide, but not its metabolite, activates the AhR in vivo.

Figure 5.Leflunomide induces aryl hydrocarbon receptor dependent expression of CYP1A1 in zebrafish. Figure 5. Leflunomide induces aryl hydrocarbon receptor dependent expression of CYP1A1 in zebrafish.

Figure 5. Leflunomide induces aryl hydrocarbon receptor dependent expression of CYP1A1 in zebrafish.Download:[11]

PPTPowerPoint slidePNGlarger imageTIFForiginal imageFigure 5. Leflunomide induces aryl hydrocarbon receptor dependent expression of CYP1A1 in zebrafish.

(A) One-cell stage wildtype embryos were injected with a control morpholino or AhR2 morpholino. At 6 hpf, the zebrafish were exposed to 10 µM leflunomide for 3 days. Immunohistochemistry for CYP1A, a known AhR2 target gene in zebrafish, demonstrated that leflunomide induces CYP1A expression in an AhR2 dependent manner. (B) Exposure of zebrafish to A771726 at doses of either 1 or 10 µM did not increase CYP1A expression.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013128.g005 Leflunomide Blocks AhR2-Dependent Fin RegenerationActivation of the AhR modulates cell differentiation and proliferation in a variety of contexts.[3], [4], [36] We previously developed zebrafish fin regeneration models to identify the mechanism by which AhR alters signal transduction pathways in vivo. Inappropriate activation of the AhR by TCDD completely abrogates tissue regeneration[8] via an AhR2-dependent mechanism.[9] AhR blocks the regenerative response by cross-talk with the β-catenin and Wnt signaling pathways.[37] To determine if leflunomide exposure would block fin regeneration via AhR2 activation, we generated AhR2 morphants, amputated the caudal fins at 48 hpf, and immediately exposed them to vehicle or leflunomide for 3 days, after which the extent of tissue regeneration was assessed by standard light microcopy. Leflunomide exposure completely blocked fin regeneration in the control morphants, but regeneration was restored in the AhR2 morphants (Figure 6A). Immunohistochemistry revealed that CYP1A was highly expressed in the leflunomide-exposed control morphants and CYP1A expression was significantly reduced in leflunomide-exposed AhR2 morphants (Figure 6A). These results demonstrate that leflunomide behaves as an AhR ligand in vivo. In contrast, A771726 was unable to activate the AhR and did not impact fin regeneration (Figure 6B). Since A771726 did not block regeneration, this suggests that the regenerative process is not responsive to dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibition, suggesting that the observed effects of leflunomide in zebrafish are independent of its metabolite, A771726.

Figure 6.Leflunomide acts through the AhR to inhibit regeneration in an AhR-dependent manner. Figure 6. Leflunomide acts through the AhR to inhibit regeneration in an AhR-dependent manner.

Figure 6. Leflunomide acts through the AhR to inhibit regeneration in an AhR-dependent manner.Download:[12]

PPTPowerPoint slidePNGlarger imageTIFForiginal imageFigure 6. Leflunomide acts through the AhR to inhibit regeneration in an AhR-dependent manner.

Amputation of the caudal zebrafish fin is a well-established model used to study tissue regeneration; TCDD is known to inhibit this regeneration process. To investigate whether leflunomide behaves like TCDD to inhibit epimorphic regeneration through the AhR, one-cell stage embryos were injected with a control or AhR2 morpholino, and the caudal fin was amputated at 48 hpf, followed by immediate exposure to vehicle or 25 µM leflunomide. (A) After 3 days, images of the fins were taken with brightfield microscopy. In addition, immunohistochemistry for CYP1A confirmed that leflunomide activated AhR2 (dotted line indicates the plane of amputation). (B) Although A771726 did not appear to activate the AhR in vivo or in our cell culture models, we investigated whether the compound could also inhibit fin regeneration, as inhibition of cell growth via disruption of de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis inhibition is a well-characterized endpoint of A771726. Amputated zebrafish were exposed to vehicle or 10 µM A771726. Exposure to 10 µM A771726 did not influence the regenerative process.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013128.g006 The AhR is not required for the anti-proliferative effects of leflunomide in primary T cellsGiven the observation that leflunomide was able to elicit an AhR-dependent inhibition of regeneration in the zebrafish model, we next asked whether AhR is involved in the immunosuppressive action of leflunomide or A771726 in CD4+ or CD8+ T cells from AhR −/− and AhR +/+ backgrounds (Figure 7A). In order to evaluate the effects of leflunomide and A771726 on cell proliferation, we confirmed that leflunomide or A771726 did not alter the viability of the analyzed cell populations compared with vehicle treatment (Figure 7B). Viable CD4+ or CD8+ T cells (Figure 7B) from AhR +/+ or AhR −/− mice were then analyzed as a function of CFSE staining to determine the number of cellular divisions that had taken place. The growth inhibitory actions of both leflunomide and A771726 in CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells were readily apparent when compared to vehicle treated cells. Leflunomide potently reduced the number of cell divisions in both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells (Figures 7C–D). Specifically, leflunomide at 5 µM suppressed the number of cells undergoing three or more divisions, whereas leflunomide at 50 µM suppressed proliferation beyond one division. (Figures 7C–D). However, no difference was observed in the growth inhibition patterns by leflunomide in cells from AhR positive or null mice (Figures 7C–D). A771726 was also able to inhibit proliferation of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, but no difference was observed between AhR +/+ and AhR −/− cells. In addition, the degree of inhibition by A771726 was similar to that of leflunomide Figures 7E–F). Together, these data suggest that neither the metabolism of leflunomide to A771726 nor their respective anti-proliferative effects could be linked to AhR activation in mouse splenocytes.

Figure 7.The AhR is not required for the suppression of murine T-cell proliferation by leflunomide. Figure 7. The AhR is not required for the suppression of murine T-cell proliferation by leflunomide.

Figure 7. The AhR is not required for the suppression of murine T-cell proliferation by leflunomide.Download:[13]

PPTPowerPoint slidePNGlarger imageTIFForiginal imageFigure 7. The AhR is not required for the suppression of murine T-cell proliferation by leflunomide.